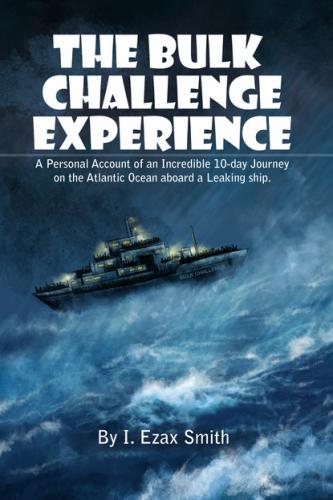

The Bulk Challenge Experience. I. Ezax Smith

nothing promising about our travel arrangement had been achieved. Nevertheless, we were not disappointed. At least we were in the port and were much safer. But then, there was nowhere to sleep. People were everywhere – in containers, offices and even in the open. Because we had many little children, we went back to Theresa’s house and retired for the day. The house was not far from the port, and the community seemed calm and not troubled by what was going on in the port. Perhaps, this apparent sense of security was because of the community’s proximity to the port and the security that the presence of the ECOMOG brought to the area.

The next day we went back to the port and repeated the check-in process. This time, it was just Cedrick and I. The rest of the family – women and children – remained home with strict instructions about what to do, just in case they observed strange movements or heard anything fishy. At the port, there was still uncertainty as to what would happen; there was no clear understanding about the ship or its departure. We began to meet several people we knew; they had now made the port their new home. These were people from our community up town, people from school, work and church. Even some distant family members were among them. I ran into some of my cousins who informed me that they had spoken to their brother who had promised to help them get out of the country if and when it was clear what the ship would do. We agreed to keep each other posted on news regarding the ship, departure and cost when the information became available. They took us to their spot, the area at the port where they now spent their days and nights. We continued to hang around an office within the port that was said to be used by the crew from Bulk Challenge. It was not a big enough ship for the crowd. If anything, it would have to be a first-come, first-serve basis, but under no circumstance could it take every one who wanted to get out. And then, we soon realized that not everyone at the port was there to get out. Some people just wanted to be in the safety reach of the peace keepers until things quieted down and they could go back to their homes, while others were there scouting for food and any other assistance they could get for their family.

One important function the Freeport served during the war years was, as market ground for food and other basic necessities. People assembled at the port each day to find food for their families. There was no telling what one might find on any given day. The goods on the market depended on contents of whatever warehouse was broken into. Sometimes there was food, which everyone needed; and sometimes such things as plates and glasses or paint, which nobody wanted. “Such was the time, such was the situation”—to quote Frank E. Tolbert, the brother of the late president, William R. Tolbert, Jr. Sadly, both had perished in the April 1980 military coup in the country. People came from nearby communities like Logan Town, New Kru Town, Clara Town and Battery Factory, to hustle for food for their families. People also came from far off places like Coca Cola Factory, Brewersville, and Central Monrovia. They left at the end of each day with whatever they could lay their hands on. Hence, it was understandable that not all the people in the port were there to leave the country. For us who had decided to leave, it was important that we kept our ears open for news of departure in order to be among the first to jump aboard. After a couple of days, we learned that the crew was considering a process to register potential passengers. I therefore managed to start a discussion and build relationship with some of the crew members. We had money to use to pay our way out of the country but did not know what it would cost for all of us. Once the word was out about the ship’s plans, my cousin – the Rev. Dr. Larry Konmla Bropleh – connected with me to include his siblings in whatever plan or arrangement I was making. Larry was the Director for African Affairs of the Baltimore-Washington Conference of the United Methodist Church. He had visited Liberia twice in 1994 and 1995, and was in regular contact with relatives and friends. We connected Larry to the shipping authorities so that he would negotiate with them on our behalf. It took a couple of days for arrangements to be finalized because it was difficult to reach Liberia by phone at the time. However, payment arrangement was discussed and concluded, and Larry instructed us to go and meet the captain pay the money we had, and he would pay the difference. The cost was $75 per person. We went and met the captain, and he confirmed the agreement, and we paid for our tickets. The Captain listed our names and gave tickets for all 14 of us, including my family of six.

We were among the first group of people to be issued tickets. So, we were indeed excited that at long last, we would finally be leaving the hostilities behind. The instruction was simple: when it was time to board, heads of households or families would be called first to stand at the entrance while members of the family would be called; in our case, the 13 others. As they entered the ship, with tickets in hand, the head of the family or group would confirm that each belonged to that group. And they would all enter. It sounded really simple but didn’t look so simple. Many people expressed fear that the growing number of people gathering to board the ship clearly exceeded the capacity of the ship. But the captain assured us repeatedly that we would be among the first to board.

There was sufficient funds — at least, enough money for the upkeep of my family for a couple of months. At the time, I worked as an Internal Auditor for the Liberia Bank for Development and Investment (LBDI). Thanks to the management who had arranged for its staff to get extra emergency money and food. By word-of-mouth, the message got around fast and we converged at the home office of a businessman at a certain location across the bridge. “Across the bridge”— the Freeport is situated on Bushrod Island, which is connected to central Monrovia by two bridges—the Waterside Bridge, referred to as the old bridge, and the Gabriel Tucker Bridge, referred to as the new bridge. Any location after the bridges is generally referred to as ‘across-the-bridge.’ At the home office, the General Manager and Comptroller paid staff and provided each of us a bag of rice. I got my pay and rice and was quite ready to get out of the country with some level of satisfaction. Although we had learned from experience how to hide money on ourselves, it was not reasonable to walk around with a whole lot of money, so I divided what I had received into two equal amounts and gave one half to my wife to hold and I held on to the other half.

The Liberia Bank for Development and Investment was one of the few surviving banks in the country and very much potent financially. Since its creation by an Act of the National Legislature in 1961, it has been one of the financial pillars of the country, perhaps because of its joint ownership by the Liberian government and major international financial institutions that purchased equity in the Bank. It is predominantly a privately owned institution under private management with a Board of Directors elected annually by its shareholders. The Bank commenced operations in 1965 as Liberian Bank for Industrial Development and Investment. Under an amendment in 1974, the name was changed to the Liberian Bank for Development and Investment (LBDI). A further amendment in 1988 allowed the Bank to engage in commercial banking activities, to complement its development objectives⁸. I was with the bank from 1993 to 1998.

With tickets in hand, and the assurances of the captain, we felt relaxed and satisfied that we would soon leave the horrors of the senseless war behind. To ensure we followed the development of the Bulk Challenge in regard to departure or any arrangement for leaving, we moved from Rebecca’s house to the port and secured an empty 40-foot container as our new home. When my wife suggested it, at first I was edgy about staying in a container, because I thought I could find one of the offices on the compound, but they were all filled. Later, I realized that we were not the only family staying in a container. Many others had been there – in the Port – since they moved from their homes a while before the resurgence of fighting that April. All through the day and sometimes in the night, we strolled around the dock waiting to hear news of the departure of the ship, but we heard nothing. Each day was embraced with optimism but ended with frustration and uncertainty. Days went by and the crew kept issuing tickets and accepting money from potential passengers.

Finally, the day arrived and an officer announced on a loud speaker that luggage would be loaded onto the ship. He directed those with tickets to move their luggage nearer to the pier, and emphasized that ticket holders needed to be available to verify their luggage and take receipt of individual recovery tickets which they would need