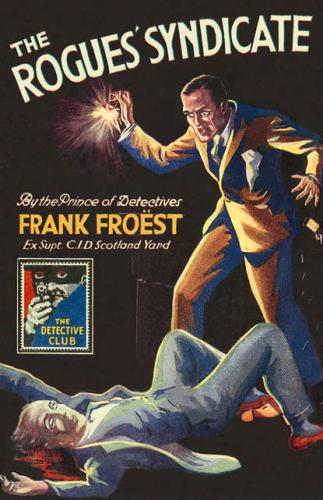

The Rogues’ Syndicate: The Maelstrom. Frank Froest

him to himself. He moved to interrupt the pursuer. As a man came into view Hallett’s hand fell on his shoulder.

‘One moment, my friend—’

An oath was spat at him as the man wrenched himself free and was blotted out in the gloom. Hallett shrugged his shoulders philosophically, and made no attempt at pursuit.

‘Alarums and excursions!’ he murmured. ‘Wonder what it’s all about?’

In nine-and-twenty years of life, Jimmy Hallett had acquired something of a philosophy that made him content to accept things as they were, save only when they affected his personal well-being. Then he would sit up and kick with both feet. His lack of curiosity was almost cold-blooded. There was, indeed, a certain inoffensive arrogance in his attitude towards the ordinary affairs of life. He was the sort of man who would not cross the road to see a dog-fight.

Yet he always had a zest for excitement, providing it had novelty. A man who had scrambled for a dozen years in a hotch-potch of vocations retains little enthusiasm for commonplaces. When Hallett senior had gone out from the combined effects of a Wall Street cyclone and an attack of heart failure, his son and heir had found himself with a hundred thousand dollars less than nothing. Young Hallett went to his only surviving relative—an elderly uncle with a liver—and, with the confidence of youth, rejected the offer of a cheap stool in that millionaire’s office. He believed he could get a living as an actor; but a five weeks’ tour in a fortieth-rate company, which finally stranded in the wilds of Michigan, convinced him of the futility of that idea. After that he drifted over a wide area of the United States. Farmhand, railwayman, cow-puncher, prospector, and one very vivid voyage as a deck-hand on a cattle boat. It was inevitable that, of course, he should eventually drift into that last refuge of the unskilled, intellectual classes—journalism. Equally, of course, it was inevitable that Fate, who delights to take a hand at unexpected moments, should interfere when he showed signs of making a mark in his profession. His uncle died intestate, and Jimmy leapt at a bound to affluence beyond his wildest dreams.

He had stayed long enough in New York after that to realise how extensive and variegated were the acquaintances who had stood by him in adversity. They took pains that he should not forget it. And forthwith he had taken counsel of Sleath, the youthful-looking city editor of ‘The Wire’, who breathed words of wisdom in his ear.

‘Go to Europe, Jimmy. Travel and improve your mind. Let the sharks forget you.’

So Jimmy Hallett stood lost in a fog, somewhere within hail of Piccadilly Circus, with an unopened package in his hand, and the memory of a girl’s voice in his mind. A less observant man than Hallett could not have failed to perceive that the girl was of a class unlikely to be involved in any street broil. The man flattered himself that he was not impressionable. But he retained an impression of both breeding and looks.

He dangled the package—it was small and light—on his finger, and moved forward till the light from a shop window gave him an opportunity of examining it more closely. It was closely sealed with red sealing wax, but the wrapping itself had apparently been torn from an ordinary newspaper. He hesitated for a moment, and then tore it open. He could scarcely have told what he expected to find. Certainly not the thirty or forty cheques that lay in his hand. One by one he turned them slowly over, as though the inspection would afford some indication of why they had been so unexpectedly thrust upon him. A bare possibility that he had been made an unwilling accomplice in a theft was dismissed as he noticed that the cheques were dead—they all bore the cancelling mark of the bank. Why on earth should the girl have been running away with the useless cheques? And why should she have so impulsively confided them to a stranger to prevent them from falling into the hands of her headlong pursuer?

Not that Hallett would have worried overmuch about these problems had the central figure been plain or commonplace. She had interested him, and his interest, once aroused in any person or thing, was always vivid.

Keen-eyed, he scrutinised the cheques in an endeavour to decipher the signature. They were all made out by the same person, and payable to ‘self’. The name he read as J. E. Greye-Stratton. Whoever J. E. Greye-Stratton was, he had drawn within three months, in sums ranging from fifty pounds to three hundred pounds, an amount totalling—Hallett reckoned in United States terms—more than fifteen thousand dollars.

He stuffed the cheques into his pocket as an idea materialised in his mind. An opportune taxi pushed its nose stealthily through the wall of fog and halted at his hail.

‘Think you can find a post-office, sonny?’ he demanded.

‘Take you anywhere, sir,’ assented the driver, cheerfully.

‘Find your way by the stars, I suppose,’ commented Hallett, the tingle of fog still in his eyes.

Nevertheless, the driver justified his boast, and his fare was shortly engrossed with the letter ‘G’ in the London Directory. There was only one entry of the name he sought, and he swiftly transcribed the address to a telegraph form.

‘Greye-Stratton, James Edward, 34, Linstone Terrace Gardens, Kensington, W.’

Shortly the cab was again crawling through the fog, sounding its siren like a liner in mid-channel. All that the passenger could make out was a hazy world, dotted with faint yellow specks, which now and again transformed themselves into lights as they drew near them. Later the yellow specks grew less as they swerved off the main road, and a moment later the car came to a halt.

The driver indicated the house opposite which they were standing, with a jerk of his thumb, as Hallett descended.

‘That’s the place, sir.’

It was little that Hallett could see of the house, save that it was a big, old-fashioned building, with heavy bow, windows and a basement protected by wrought-iron rails. There was no light in any part of the house, not even the hall. Twice the young man wielded the big, brass knocker, arousing nothing apparently but an echo. As he raised it a third time the door was thrown open with disconcerting suddenness, and he was aware of someone standing within the blackness of the hall. Hallett could distinguish nothing of his features.

‘I wish to see Mr Greye-Stratton,’ said Hallett, and tendered a card.

The other made no attempt to take it.

‘He won’t see you,’ he declared, with harsh abruptness, and only a sudden movement of Hallett’s foot prevented the door being slammed in his face.

His teeth gritted together, and he thrust the door back and himself over the lintel. He was an easy-tempered man, but the deliberate discourtesy had roused him to a cold anger.

‘That will do, my man,’ he said, clipping off each word sharply. ‘I want ordinary civility, and I’m going to see that I get it. My name is Hallett—James Hallett, of New York. Now you go and tell your master that I want to see him about certain property of his that has come into my hands. Quick’s the word!’

There was a pause. When the man in the hall spoke again his tone had changed.

‘I beg your pardon, Mr Hallett. It is dark—I mistook you for someone else. I am sure Mr Greye-Stratton would have been happy to see you, but unfortunately he is ill. If you will leave whatever you have, I will see that it reaches him. By the way, I am not a servant. I am a doctor. Gore is my name.’

Hallett thrust his hand in the pocket that contained the cheques. He had no intention of handing them over without some information about the girl in black. And he fancied he detected a note of anxiety in the doctor’s voice, as though, while forced in a way to civility, he was anxious for the visitor to go.

‘I quite understand, Dr Gore,’ he said, coldly. ‘I will call at some other time. I should like to return the property to its owner in person—for a special reason. Good-night!’

‘Then you will not entrust whatever you have to me?’

‘I would rather see Mr Greye-Stratton at some future time.’

He half turned to go.

‘One moment.’ The doctor laid