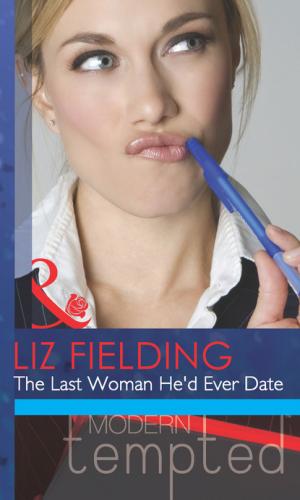

The Last Woman He'd Ever Date. Liz Fielding

complaints about her disregard for the by-laws if he’d been seriously hurt. It wasn’t a comfort. ‘I’m so sorry I ran into you.’ And she was. Really, really sorry.

Sorry that her broad beans had been attacked by a blackfly. Sorry that she’d forgotten Archie’s apple. Sorry that Mr Grumpy had been standing in her way.

Until thirty seconds ago she had merely been late. Now she’d have to go home and clean up. Worse, she’d have to ring in and tell the news editor she’d had an accident which meant he’d send someone else to keep her appointment with the chairman of the Planning Committee.

He was going to be furious. She’d lived on Cranbrook Park all her life and she’d been assigned to cover the story.

‘It’s bad enough that you were using it as a race track—’

Oh, great. There you are lying in a ditch, entangled with a bent bicycle, with a strange man’s hand on your backside—he’d better be trapped, too—and his first thought was to lecture her on road safety.

‘—but you weren’t even looking where you were going.’

She spat out what she hoped was a bit of twig. ‘You may not have noticed but I was being chased by a donkey,’ she said.

‘Oh, I noticed.’

Not sympathy, but satisfaction.

‘And what about you?’ she demanded. Although her field of vision was small, she could see that he was wearing dark green coveralls. And she was pretty sure that she’d seen a pair of Wellington boots pass in front of her eyes in the split second before she’d crashed into the bank. ‘I’d risk a bet you don’t have a licence for fishing here.’

‘And you’d win,’ he admitted, without the slightest suggestion of remorse. ‘Are you hurt?’

Finally…

‘Only, until you move I can’t get up,’ he explained.

Oh, right. Not concern, just impatience. What a charmer.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she said, with just the slightest touch of sarcasm, ‘but you shouldn’t move after an accident.’ She’d written up a first-aid course she’d attended for the women’s page and was very clear on that point. ‘In case of serious injury,’ she added, to press home the point that he should be sympathetic. Concerned.

‘Is that a fact? So what do you suggest? We just lie here until a paramedic happens to pass by?’

Now who was being sarcastic?

‘I’ve got a phone in my bag,’ she said. It was slung across her body and lying against her back out of reach. Probably a good thing or she’d have been tempted to hit him with it. What the heck did he think he was doing leaping out in front of her like that? ‘If you can reach it, you could dial nine-nine-nine.’

‘Are you hurt?’ She detected the merest trace of concern so presumably the message was getting through his thick skull. ‘I’m not about to call out the emergency services to deal with a bruised ego.’

No. Wrong again.

‘I might have a concussion,’ she pointed out. ‘You might have concussion.’ She could hope…

‘If you do, you have no one but yourself to blame. The cycle helmet is supposed to be on your head, not in your basket.’

He was right, of course, but the chairman of the Planning Committee was old school. Any woman journalist who wanted a story had better be well-groomed and properly dressed in a skirt and high heels. Having gone to the effort of putting up her hair for the old misogynist, she wasn’t about to ruin her hard work by crushing it with her cycle helmet.

She’d intended to catch the bus this morning. But if it weren’t for the blackfly she could have caught the bus…

‘How many fingers am I holding up?’ Mr Grumpy asked.

‘Oh…’ She blinked as a muddy hand appeared in front of her. The one that wasn’t cradling her backside in a much too familiar manner. Not that she was about to draw attention to the fact that she’d noticed. Much wiser to ignore it and concentrate on the other hand which, beneath the mud, consisted of a broad palm, a well-shaped thumb, long fingers… ‘Three?’ she offered.

‘Close enough.’

‘I’m not sure that “close enough” is close enough,’ she said, putting off the moment when she’d have to test the jangle of aches and move. ‘Do you want to try that again?’

‘Not unless you’re telling me you can’t count up to three.’

‘Right now I’m not sure of my own name,’ she lied.

‘Does Claire Thackeray sound familiar?’

That was when she made the mistake of picking her face out of the bluebells and looking at him.

Forget concussion.

She was now in heart-attack territory. Dry mouth, loss of breath. Thud. Bang. Boom.

Mr Grumpy was not some irascible old bloke with a bee in his bonnet regarding the sanctity of footpaths—even if he was less than scrupulous about where he fished—and a legitimate grievance at the way she’d run him down.

He might be irritable, but he wasn’t old. Far from it.

He was mature.

In the way that men who’ve passed the smooth-skinned prettiness of their twenties and fulfilled the potential of their genes are mature.

Not that Hal North had ever been pretty.

He’d been a raw-boned youth with a wild streak that had both attracted and frightened her. As a child she’d yearned to be noticed by him, but would have run a mile if he’d as much as glanced in her direction. As a young teen, she’d had fantasies about him that would have given her mother nightmares if she’d even suspected her precious girl of having such thoughts about the village bad boy.

Not that her mother had anything to worry about where Hal North was concerned.

She was too young for anything but the muddled fantasies in her head, much too young for Hal to notice her existence.

There had been plenty of girls of his own age, girls with curves, girls who were attracted to the aura of risk he generated, the edge of darkness that had made her shiver a little—shiver a lot—with feelings she didn’t truly understand.

It had been like watching your favourite film star, or a rock god strutting his stuff on the television. You felt a kind of thrill, but you weren’t sure what it meant, what you were supposed to do with it.

Or maybe that was just her.

She’d been a swot, not one of the ‘cool’ group in school who had giggled over things she didn’t understand.

While they’d been practising being women, she’d been confined to experiencing it second-hand in the pages of nineteenth-century literature.

He’d bulked up since the day he’d been banished from the estate by Sir Robert Cranbrook after some particularly outrageous incident; what, she never discovered. Her mother had talked about it in hushed whispers to her father, but instantly switched to that bright, false change-the-subject smile if she came near enough to hear and she’d never had a secret-sharing relationship with any of the local girls.

Instead, she’d filled her diary with all kinds of fantasies about what might have happened, where he’d gone, about the day he’d return to find her all grown up—no longer the skinny ugly duckling but a fully fledged swan. Definitely fairy-tale material…

The years had passed, her diary had been abandoned in the face of increasing workloads from school and he’d been forgotten in the heat of a real-life romance.

Now confronted by him, as close as her girlish fantasy could ever have imagined, it came