Grizzlies, Gales and Giant Salmon. Pat Ardley

water. After tying up the skiff, I joined him where he stood ringing his hands while I was wishing that I had an axe to help it sink the rest of the way. There were a few things floating up to the windshield, and in the flashlight beam I could all too clearly envision myself floating up to that window with a silent scream on my face. There was nothing we could do in the dark so we went to bed.

The next morning, George found a spot in the bay where the tide went out and left a natural beach that would support the OM. At low tide, he built a crib that would hold the boat upright as the tide went out around it. Then he cut down two alders hoping to use them to help keep the boat floating, but they barely floated themselves. He then borrowed two buoyant cedar logs from John and strapped them to the sides of the boat so he could tow it to the crib on the beach. He had to wait until the next high tide to move the boat. Finally, about an hour before high tide, he cut through the ropes that were holding the OM to the side of our float. It didn’t sink any further. That’s too bad, I thought.

Then he towed it over to the spot he had prepared and tied it to the trees that were hanging off the shore. As the tide went out, water poured from hundreds of different places on the sides of the boat. We had borrowed a pump to drain the water out as the tide went down, but we didn’t have to use it. This was not a good sign, confirming my opinion that this boat was definitely not seaworthy.

We borrowed a small empty float that belonged to another fishing resort. It was in Sunshine Bay for the winter for safekeeping. George worked day after day, building a proper cradle to hold the OM upright after it was pulled onto the float. He used his brand-new chainsaw and cut down several small trees and also used the first two alders that he cut down. When the boat was empty of water, and before the tide came back in, John helped pull the boat up onto the float with his tugboat. He used lots of ropes tied carefully into a harness and around the OM to protect the boat so it wouldn’t fall apart as he pulled it out of the water. I was somewhat dismayed by the care he took, as I was hoping that it would crumble with the force of the pull. George then built a frame around it, which he covered with plastic so the whole boat could dry out.

Once in a while I made dinner for John and another friend Warren Nygaard, who also lived in Sunshine Bay. The two fellows would come over for supper, and then through the evening we would play hearts, which I usually won. The three guys were all very competitive and watched the cards being played while I was up and down getting tea or treats and chatting while I had a captive audience. I never paid much attention to the cards, and this kept the fellows constantly guessing about my strategy and me constantly winning. Sometimes I won just because I ended up with 101 points, which is an automatic win! One afternoon I made a Chinese food dinner for the four of us. I spent three hours chopping, slicing, stirring, mixing and sautéing. We sat down to dinner and the food was gone in less than three minutes. What on earth had I just spent three hours on?! I don’t know if anyone even tasted it. But it was worth the work to be entertained by Warren’s stories of growing up in the wilderness of Rivers Inlet and the long Robert Service poems that John memorized while he was towing a boom of logs for thirty hours at a time.

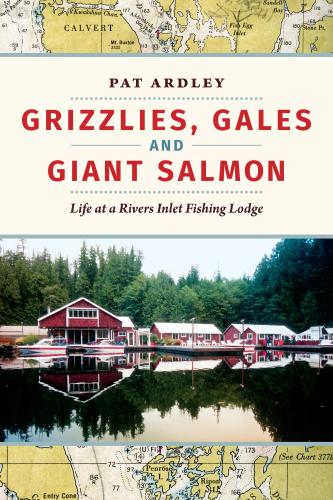

The ill-fated OM hauled out on a borrowed float. George thought I should help work on it but I never had the confidence that this boat would ever safely carry us without sinking.

Other than winning at hearts and cooking or serving tea, it was hard to get noticed when I was always surrounded by men who were logging or fishing or hunting, or doing any number of real “men’s pursuits.” I spent a lot of time alone in the cabin, and when someone arrived I would be so excited and anxious for some real conversation that I would become tongue-tied. I usually sat quietly listening to all the guy talk, and when I did speak up, the fellows would turn to look at me and then get right back into their own stories. Every so often I would start talking and then they would all turn and stare. Then I would lose my train of thought and stop mid-sentence. I needed to do something or I would go crazy. I observed the men in conversation over time and learned a few tricks. When I felt I really had something to say, I would step one foot into the group, lean forward and speak in a loud voice about the “lube job that I was doing on my sewing machine.” This would be enough to catch their attention, and then I could launch into what I really wanted to say. Once I had them, I had to talk quickly or I would lose their attention.

We had met an older couple, Ed and Dottie Searer, when we were working for the resort the previous summer. One day we saw them again at the store and they invited us to visit them and stay overnight. We drove our skiff up to their cabin at the head of the inlet on the side of the Wannock River. Ed had been a TV announcer in the States and they had retired to the inlet for a change of pace. They introduced us to the most amazing breakfast: fried bacon, scrapple fried in the bacon fat, fried eggs, biscuits and gravy—made from the bacon drippings and a can of condensed milk—and toast. Dottie’s scrapple was made from cornmeal mush and the meat and gel from pork hocks boiled for hours. These ingredients were ground all together with spices. We poured syrup on the scrapple after it was fried, just for good measure. It was an authentic Deep South breakfast and absolutely delicious, but you really needed a four-hour nap after eating it.

Ed was an amazing fisherman. In the summer, they catered to paying guests who came from the States to have Ed guide them to the huge chinook waiting to spawn in the Wannock River. He always seemed to have the best luck. Possibly luck and skill—with a little deviousness thrown in. He had a boat that was painted green on one side and yellow on the other. One of his best tricks was to motor slowly away from the rest of the fishing boats as soon as he had a fish on the line. He would hold his fishing pole underwater so that no one could tell that he had hooked a fish. Once he was away from the tourists, he would turn his boat so the other colour was showing. People would usually only be fishing at the head for a couple of days so were never able to figure out exactly where he hooked into the big ones.

There was another couple who also lived in Sunshine Bay that winter. Bob and Joan Ryder lived on their own classic wood cruiser and were the caretakers for the American-owned Rivers Inlet Resort. Bob told us that he had helped train commandos who were involved in the Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961. He liked to throw cans and bottles out into the water, and after they had drifted for a few minutes he would blast away at them with an automatic rifle. Warren and I traded notes about how we would dive into our cast iron bathtubs when we heard him start shooting. Bob also said that he was suspicious of anyone entering our bay. He said, “I watch the boat approaching through the scope on my rifle, ready to shoot if I don’t trust the look of it.”

Small Boat, Deep Water

I decided that I needed to overcome my fear of being in boats on the ocean. I wouldn’t last very long in Rivers Inlet if I couldn’t comfortably travel around in them. We were surrounded by islands, and if you did go to shore, you didn’t exactly walk around as much as slog, slip and scrabble through the underbrush, and over or under fallen logs and up and down ravines. There are no roads in Rivers Inlet. If you want to get from one place to another, you have to go there by boat. Most people lived miles apart and on separate islands. I use the term “most people” loosely since there were fewer than fifteen people living at the mouth of the inlet at that time.

Growing up on the Prairies I loved nothing more than to walk for hours out of town into the dry, dusty, flat fields. You could see all around you and miles away to where the horizon is swallowed up into the sky. I felt that I could see forever when I stared out the window of my elementary school class. From my desk, I could see one little copse of trees on the otherwise bald prairie and once watched a deer dive into the bush to hide in the only cover for miles in any direction.

I have a long stride. George always hurried to keep up when we walked together on a city street because his stride was short and uneven from his years of scrabbling through the coastal bush, and I had trouble keeping up with him when we headed onto shore and up into the woods.

I’m a Pisces, but having the sign of the fish doesn’t help me here. I learned from my first big boat trip that the ocean is something to be feared and now I had to try to unlearn this. I wanted to be able to help George rebuild and refinish the OM, but unless I could get a better feeling about being in