The Ticket That Exploded. William S. Burroughs

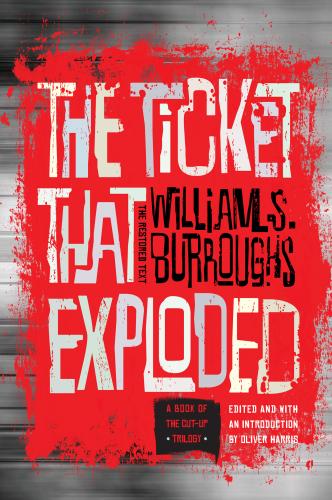

identity. Thematically, it was all a masque, and we are such stuff as dreams are made on. Formally, in making the transition from anonymous print to artist’s pen—and we notice that Gysin signs with his initials—the calligraphy echoes the unexpected switching of type and script on the Olympia Press jacket cover. There, beneath Sommerville’s photo-collage, the book title is written in large red ink in Burroughs’ own distinctive script above his name, while his name is not signed by hand but perversely typed in black block capitals. The cover by Kuhlman Associates for Grove in 1967 was also typographically striking, producing various letters out of a hat that seems to belong to Charlie Chaplin, but neither the comic tone nor the Dada-esque design has anything to do with the artwork inside the book or with questions of authorship and identity.40

The final feature that makes the ending of the Olympia edition so intriguing is the precise transition between Burroughs’ text and Gysin’s drawing. The transition not only silences language but spatializes time, as the temporal march of words from left to right gives way to a spatial arrangement. This farewell to Time draws attention to what lies beyond words literally on the page, as the 1962 Ticket ends with the word “good-bye —” hyphenated and split at the end of the line, so that all six lines of text on the final page end with either an em dash or a hyphen:

tain wind of Saturn in the morning sky —

From the death trauma weary good-bye then” —

Hassan i Sabbah: “Last round over —

Remember i was the ship gives no flesh ident-

ity — Lips fading — Silence to say good-

bye —

The effect of these solid lines one above the other is to resemble the first hexagram of the I Ching—Ch’ien (The Creative), made up of repeated trigrams for “Heaven.” Burroughs and Gysin were familiar with how the ancient Chinese system of divination had been used as a method of chance composition—most famously in music by John Cage since the 1950s—and because nowhere else in The Ticket are so many horizontal lines stacked like this, the ending seems to simultaneously identify the creative principle of the text and abandon it in a single gesture. Significantly, the text’s one-word final line ends without any closing speech marks, so that the last em dash points with a straight line into empty space. Immediately below this final line, Gysin’s script and calligraphy begin, the right side of which ends with a series of horizontal lines paralleling the printed em dashes and hyphens of the typed text above it, so creating a second potential hexagram. However, the most important element is simply that Gysin’s calligraphy is reproduced beneath the last typed words on the same page, which is also the final leaf in the book. The closer you analyze it, the more perfect the fusion of type and script seems to become. But again, was any of this intentional?

On the last page of his 1962 typesetting manuscript Burroughs signaled his attention to visual detail by typing, rather than his usual two dashes, five dashes after the final word “good-bye,” indicating his aim to end with an especially elongated line. The archival record also shows that the key feature of the Olympia Press design—the printing of Gysin’s artwork immediately after his text to form a single and complete last page—was not some happy accident. On the contrary, an editor at Olympia put a note on the penultimate sheet of the page proofs requesting that lines of text be moved precisely in order to make this happen: “faire passer au moins 4 ou 5 lignes à la p. 183.”41 As regards the actual layout of text on the last page of the Olympia edition, with its striking line-up of dashes and hyphens, there’s no evidence to suggest that this was determined by anything more than the number of words and the narrow line width. In which case, the hexagram of lines for Heaven was the product of a material accident, which is entirely fitting given the role of chance in the philosophy and practice of both the I Ching and cut-up methods. We are left not with a choice between meaningful creativity or meaningless mysticism but with a way of reading beyond the binary of belief and skepticism.

The 1967 Grove Press edition dramatically changed the book’s ending. The addition of new material made the last section five times longer, while the final paragraph shifted the tone and created a sense of circularity by echoing lines of speech from the book’s opening section. The last paragraph also ended with a new final phrase, closed by speech marks: “Are you listening B.J.?’” The typed words were now separated off from Gysin’s script, which, in the most radical change, was reproduced on the facing leaf. And finally, this was no longer the final leaf in the book, since it was followed by “the invisible generation” Appendix, a text without punctuation that concluded with words from The Tempest (“into air into thin air”) followed by empty silent space.

In different ways, the Olympia and Grove editions of The Ticket created complex open endings, and given the book’s project to transcend time, it would be ironic to fetishize the past and deny change by repeating the products of particular historical circumstances. This edition ends by making choices that point in contrary directions—cutting “the invisible generation” essay as an appendix of historical interest (key passages are referenced in the Notes; the full text is available elsewhere)42 and restoring the integration of Gysin’s calligraphy as the book’s great transcendent gesture. After all the lyrics and melodies in The Ticket, all the “vaudeville voices,” “riot noises,” “sounds of lovemaking,” “City sounds,” “jungle sounds,” “crackling static,” and “sound of feedback,” the composite formed by print and script ends the most musical book of the Cut-Up Trilogy on a soundless note. The book silences the noisy lusts of life, stops the fairground circus that stupidly spins us round and around, and takes its leave with an open-ended vision of an elsewhere. A book of paradoxes—cynical yet elegiac, polemical but poetic, obscene and spiritual—The Ticket ends by visualizing silence, a vital space of possibility beyond words, “where the unknown past and the emergent future meet in a vibrating soundless hum.”43

Oliver Harris

July 1, 2013

1. Burroughs to Gysin, July 26, 1960 (William S. Burroughs Papers, 1951–1972, The Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection of English and American Literature, New York Public Library, 85.2; after, abbreviated to Berg).

2. Burroughs “Voices in Your Head,” introduction to You Got to Burn to Shine, by John Giorno (London: Serpent’s Tail, 1994), 6.

3. Undated typescript, circa 1960, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

4. Iggy Pop interviewed by David Fricke in Rolling Stone (April 19, 2007), 59.

5. Brion Gysin in Minutes to Go, by Sinclair Beiles, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Brion Gysin (Paris: Two Cities Editions, 1960), 5.

6. Burroughs to Gysin, October 25, 1966 (Berg 86.9).

7. Burroughs to Seaver, July 21, 1964 (Berg 75.1).

8. Undated typescript, circa 1960 (Berg 48.22).

9. Burroughs Live: The Collected Interviews of William S. Burroughs, 1960–1996, edited by Sylvère Lotringer (New York: Semiotext(e): 2000), 80.

10. Undated typescript, circa 1962 (Berg 20.50).

11. Burroughs, Naked Lunch: the Restored Text, edited by James Grauerholz and Barry Miles (New York: Grove, 2003), 194, 251. For the definitive study of musical references in the text, see Ian MacFadyen’s “A Little Night Music” in Naked Lunch@50: Anniversary Essays (Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 2009).

12. Burroughs, Queer: 25th Anniversary Edition (New York: Penguin, 2010), 118.

13. Alan Ansen, William Burroughs (Sudbury: Water Row Press, 1986), 22.

14. Burroughs, “The Dead Star,” My Own Mag 13 (August 1965), 12.

15.