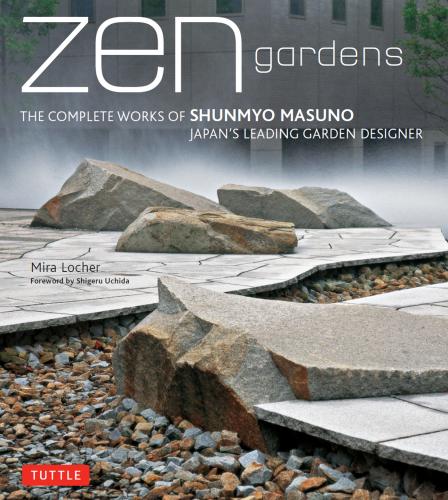

Zen Gardens. Mira Locher

be adapted to a particular context. For example, in the Kantakeyama Shinen garden at the Samukawa Shrine, Masuno features a waterfall in the dan-ochi (stepped falls) style, while in the garden at the Kyoto Prefectural Reception Hall, he incorporates a nuno-ochi (“cloth veil” falls) waterfall. Each such traditional element is chosen for its particular visual and auditory role within the specific garden. It is Masuno’s design skill that brings together these traditional elements in a unified and balanced composition that imparts an aesthetic of elegance, beauty, simplicity, and rusticity.

In the Keizan Zenji Tembōrin no Niwa at the Gotanōji temple, a gravel stream cuts through moss-covered mounds punctuated with large roughly textured rocks.

With this close connection to the formal elements of historic gardens, the traditional Japanese garden plays a distinct role in contemporary life. Industrialization and human progress have produced an enormous number of new materials and design ideas, yet it is clear from Shunmyo Masuno’s prolific practice that there still is a desire to build new gardens in the traditional style. It must be more than mere nostalgia for the old ways of doing things that inspires clients to request a traditional garden or inspires Masuno to design one. Certainly, in the case of a garden at a Buddhist temple, it is logical to expect a traditional garden if the temple buildings are constructed in a traditional style, such as those at Gionji and Gotanjōji. However, for a private client with a contemporary house, as is the case of the Shojutei and Chōraitei gardens, the style of the garden is not required to mimic the style of the architecture but must complement it. The traditional garden is desired not specifically for its style, but rather for its ability to connect the owners with nature and in doing so provide both a sense of tranquility and an opportunity for deep self-reflection.

This connection to nature and the sense of serenity and self-reflection that accompany it go back to the inherent role of nature in Japanese culture, born out of the conditions of the natural environment in Japan. At the same time, the time-honored elements and symbols of traditional Japanese gardens continue to create the invisible qualities of “restrained elegance, delicate beauty, elegant simplicity and rusticity.”

SŌSEIEN

RETREAT HOUSE KANAGAWA PREFECTURE, 1984

The stone-paved approach to the guesthouse at Sōseien creates the feeling of wandering along a forested mountain path.

Nestled on a hilltop with long views to the surrounding mountains, the garden was named Sōseien by the owners, meaning “refreshing clear scenery.” Serving three different functions, the tripartite garden encircles the guesthouse run by the Tokyo Welfare Pension Fund and leads down the hill as the entry path. First, the entry path sets the mood, giving the visitor a sense of winding through deep mountains. Next the main garden opens out from the lobby and restaurant spaces with a series of low horizontal layers that mimics cloud formations and draws in the nearby mountains. Finally, the garden viewed from the traditional Japanese baths provides a more private, secluded scene of nature highlighted with a swiftly flowing waterfall and a quiet pond.

Flat stones in a random informal (sō), pattern form the surface of the entry path. Large stones commingle with small ones as the path meanders up the gentle slope. Closely trimmed bushes interspersed with multihued trees and a few large rocks are carefully positioned to appear natural and provide changing focal points along the path. Before long, a glimpse of the building emerges among the greenery. While the end of the path is visible, the main garden is not yet revealed, giving a feeling of pleasant anticipation. This sense of a relaxed tension, created during the walk up the path, allows both a physical and a mental transition. While physically moving up the hill, the mind is invited to take in the surrounding nature and release the cares of the day. The sensation of relief combined with expectation increases with each step closer to the guesthouse.

The design principle of shakkei (borrowed scenery) is used to incorporate the distant mountains into the composition of the garden, as viewed from the lobby.

A layer of gravel creates the transition between the guesthouse and the garden and also functions to absorb rainwater dripping off the eaves.

A sequence of entry spaces continues that transition from outside to in and from the activity of daily life to relaxation. Once inside the guesthouse, a right turn into the lobby opens up a vista of the main garden with the mountains beyond. Designed to bring the faraway views of the mountains into the garden—a design principle known as shakkei (borrowed scenery)—the main garden features a grassy lawn interspersed with low, cloud-like layers of closely clipped hedges and a few strategically placed trees and rocks. The low mounds of dense hedges are made up of many different types of plants, primarily yew and azalea, chosen for their varied seasonal colors. At the end of one central mound, a low dark angled rock interrupts the soft flow of the greenery. This abrupt change captures the viewer’s attention, allowing for a more focused awareness of the garden as a whole. A slightly taller row of hedges forms the boundary of the garden, containing the lawn and hedge-clouds and defining the fore-, middle-and background of the view. The long vistas with layers of horizontal space give the sense of being in the sky, floating among the clouds near the mountaintops.

When viewed from the bathing areas, the spaces of the garden constrict, with the trees, rocks, and ground cover reflected in a small pond and the mountains visible between the trees.

The hedges are planted and trimmed to appear monolithic in their cloud-like forms, but they consist of many different types of plants, which give variety in their leaf shapes and colors throughout the seasons.

The site plan of the Sōseien retreat house shows the open areas of the garden relating to the public spaces of the building and the more compact garden spaces near the private areas.

The rough texture and dark color of the rocks in the foreground provide contrast to the gentle slope, curved forms, and muted colors of the hedges and distant mountains.

While the main garden is open, with expansive vistas accented by low mounds of hedges, the garden viewed from the baths allows only momentary glimpses of the mountains beyond. Evergreen and deciduous trees, planted to give privacy while not completely blocking the view, form the background of the compressed spaces of the garden. A stream meanders along rocky banks toward a waterfall, which opens out into a pond in the foreground. The curves of the stream together with the fingers of land create layers of space, giving the garden a feeling of depth and great size. Bushes, ferns, and ground cover are closely planted to reflect the dense vegetation of a lush mountain scene. They vary in scale to support the concept of spatial layering—an important design principle executed differently in each of the three parts of Sōseien.

The layering of space in the Sōseien garden produces a sense of spatial depth that stimulates the viewer’s imagination. “Making people imagine the part they can’t see brings out a new type of beauty.”1 The three varied parts of the Sōseien garden allow the viewer three different ways to exercise the imagination, experience this sense of beauty, and reconnect with nature.

銀鱗荘

GINRINSŌ

COMPANY GUESTHOUSE

HAKONE, KANAGAWA PREFECTURE, 1986