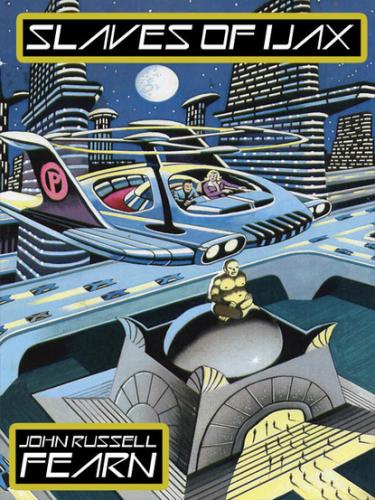

Slaves of Ijax. John Russell Fearn

that, as your scientist Einstein explained. In the laboratory where you awoke, twin gravitational stresses—opposing warps—had just ripped the sphere asunder. You did not instantly pass into unguessable age and become dust because your energy had not been dissipated: it had been held motionless, just as molecules are motionless in the infinite zero of space, yet come to life when radiation excites them. The imprisoned balanced energies escaped into the random energies in the laboratory. You understand?”

“It surprises me that the rupture didn’t kill me,” Peter mused. “I mean the sphere must have exploded with terrific force.”

“You were perfectly safe because the energy flowed outwards from the centre, in which you were situated unharmed.”

“Uh...huh....” Peter nodded slowly and then felt in the pockets of his robe with growing impatience. Mark Lanning watched him for a while then raised an inquiring eyebrow.

“Something you are seeking, Excellence?”

“Yes—a cigarette. I’m used to one after a meal.”

Lanning smiled and motioned to a robot. It went out of the room and, evidently instructed beforehand through telepathic command, returned presently with a single pellet in the centre of a blue metal tray. Peter contemplated it in surprise.

“Eat it,” Lanning «aid.

Peter picked it up and swallowed it. When the acid taste had gone from his mouth and the thing had dissolved the desire for a cigarette had vanished too.

“Nicotine counteractive,” Lanning explained. “You will never wish to smoke again. We use them for recessive units who are liable to appear now and then in any community. Some of them crave nicotine like their ancestors and are cured as you have been.”

Peter sighed and rubbed his intensely smooth chin pensively.

“So,” he said, sitting back in his chair, “I am by popular acclaim the head man in the world, eh? Well, what am I supposed to do?”

“Nothing,” Lanning answered quietly. “I am your Adviser-Elect. As in olden times a king too young to govern had a Regent, so I fill a similar position.”

“You mean that you really rule, and that I am just the figurehead?”

“In a sense, yes. But I am not the actual head of the Western Federation—that authority lies in the hands of President Valroy of the Governing Council. I am the leader of the scientists, hence my title. You are as a monarch is to Parliament—the head of the State, but not necessarily in a position to give orders that the Council does not approve. I would suggest, Excellence, that because a legend has deified you, you should accept the amenities of the position and...ask no questions.”

Peter grinned and scratched his eyebrow thoughtfully.

“The trouble is Mr. Lanning, I’m not that kind of person! I can’t take things for granted, and never could. I have to see for myself what makes things tick.”

“Indeed?” Lanning murmured, with obvious indifference. “I do hope we are not going to have differences so early in our acquaintanceship?”

Peter hesitated. “No, no reason why...only....”

“Excellence, circumstances—and the revenge of this Michael Blane you have spoken of—have placed you in a world as different from your own as anything you can conceive. You cannot hope to understand a fraction of it—its policy, its purpose, the great Task to which the people have dedicated themselves for the last three years. You cannot understand the complicated legal procedure that produced the Eastern and Western Federations and destroyed the threat of war forever. On the scientific side such things as advanced quantum-mechanics, time-and-space quadrants and similar researches are obviously beyond your knowledge. You have said yourself that you are not a scientific man.”

“Maybe so, but I lived in a pretty scientific age. The same scientific principles must still apply.”

Lanning shook his head. “I don’t think you realize how much science has changed. Take atomic power, for instance. Your era still clung to ideas of particle physics. That resulted in the release of dangerous radioactivity as an undesirable by-product. We do use atomic power extensively today, but it is not the primitive and limited usage of your Earth scientists. The atom itself is forever unknowable—all theories about it are merely analogies or models. Your era constructed a model based on the apparent duality of light—both particles and waves. This led your scientists up a blind alley of atom-smashing that almost destroyed humanity when atomic war broke out. It lasted six months with no side winning and civilization in ruins. The survivors picked themselves up and then formed a world government devoted to scientific pursuits without thought of further war. So scientists developed completely different ideas about what atoms are. Our research has been purely along the lines of electromagnetic force, of which we have made ourselves the masters. Every power we possess is derived from this basic force of the universe. But our atomic power is free from radioactivity, being derived from copper rather than uranium.”

“Copper?” Peter echoed, then he shook his head and smiled ruefully. “Well. I can still learn. After all, since I am the head—or at any rate the figurehead—of the world, I might as well make hay while the sun shines.”

“Hay?” Lanning repeated absently. Then he shrugged, “Some idiom of your own time, I presume? If you mean that you hope to institute certain ideas of your own, I can suggest that you refrain. It would not be considered...ethical.”

Peter got to his feet pensively, strolling over to one of the windows with hands clasped behind him. The robe he was wearing was softer than finest silk against his skin.

“Language and names haven’t altered much in seven centuries, Mr. Lanning,” he commented, staring out over the grey world he had come so mysteriously to rule.

“Great Britain and the United States of America spoke approximately the same language in your day,” Lanning responded. “It was decided that since their language was used by the majority of people it should become the world-language.... As to names, it takes many generations—far more than seven centuries—to change a patronymic, and even longer for a Christian name.”

“And people and customs?” Peter murmured, his eyes on a wingless airliner as it swept majestically down from the heights. “Have they changed much since my day?”

“The most changeless thing in the Universe is human nature, Excellence....” Peter was aware of the tall scientist standing near him, his hands hidden in his sleeve-ends once again. “The men and women of today still love each other, marry, and beget. They live longer than in your day—on the average a hundred and twenty years. Medical science has given them perfection; mechanical science does everything for them. They need not stir to do a thing with the robots always at hand, tireless, obedient.”

“Yet you said everybody was engaged on a great Task,” Peter remarked. “What Task?”

The eyes of the Twenty-First Century met those of the Twenty-Eighth and for a moment both of them seemed to sense the gulf between them. Then Lanning raised and lowered slender shoulders.

“It is simply an end to which all of us are working,” he said ambiguously. “If we didn’t—for everything else is done for us, remember, mental and physical torpor would paralyze us. We just have to have something to think about.”

Peter reflected that either Lanning didn’t want to explain the nature of the Task or else he was not really sure of its meaning himself. There was something about the Adviser-Elect he could not understand—an evasiveness, a coldly mechanical quality, yet despite these drawbacks he somehow liked the man.

“Have you any particular desire, Excellence?” Lanning asked presently. “If so., I will attend to it; then I am afraid I shall have to leave you for a while on urgent business.”

“By all means, you carry on,” Peter agreed. “I’ll look after myself—probably go for a walk and get orientated.”

“That,” Lanning