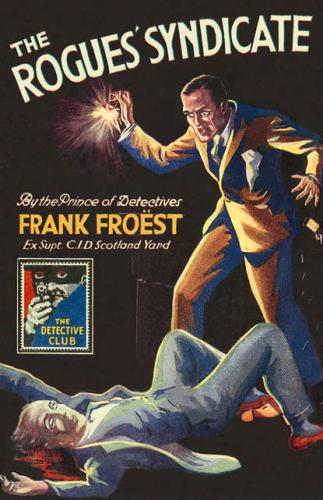

The Rogues’ Syndicate: The Maelstrom. Frank Froest

for the most part—separated. Only the girl of the cheques remained behind. As the room emptied, she walked towards Menzies.

‘That’s over, Miss Greye-Stratton,’ he said cheerfully. ‘I am ever so much obliged to you. I want you to know Mr Hallett, the gentleman who first called our attention to the death of your father.’

Jimmie concealed the surprise that the name gave him. Although there was a certain touch of melancholy in the oval face, there was none of that grief which might have been expected in a girl who had suddenly learned of the murder of her father. For a moment he was repelled. He murmured some conventional phrase of sympathy, but she swept it away as though aware that her manner needed explanation.

‘Yes, this is very dreadful, Mr Hallett, but not so dreadful to me as it might have been. You see, I scarcely knew my father. We were almost complete strangers.’

‘Miss Greye-Stratton called on me at the Yard as soon as she heard of the murder,’ interposed Menzies. ‘I thought it as well, in the circumstances, that there should be no ground for misunderstanding. You see, your story of the way the cheques came into your possession is bound to cause talk when you give evidence at the inquest. I wanted it to be definitely clear that Miss Greye-Stratton was not the lady, and she was good enough to consent to this arrangement.’

Hallett wondered how the diplomacy of the detective would have got over the difficulty if the girl had refused. That she had consented showed nerve, for she had not known that he would not identify her. He was curious, too, as to what would have happened if he had picked her out. Would she have been arrested on suspicion?

‘If it had been Miss Greye-Stratton, she would hardly have sought you out,’ he remarked.

‘No, no; of course not,’ said Menzies soothingly. ‘I never thought for a moment that she was the woman. One likes to save anything in the nature of scandal, though. I remember a case where two elderly ladies—sisters—living in a country house were attacked by someone with a hammer. One was found dead, the other unconscious—she remained unconscious for weeks. The hammer was found in an outhouse a hundred yards away. Now, there was a considerable amount of gossip, and the theory was firmly held by dozens of people that the living sister had attacked the dead one. They overlooked the fact that to have done so she must have walked to the place where the hammer was found after her own injuries had been inflicted. That’s an example of what I mean.’

The girl nodded.

‘I am quite sure you only meant to save me possible future unpleasantness. Is there anything else? You have my address.’

‘There is no other way at the moment in which you can help. As matters develop, I may call on you. It has been very good of you—’

She stretched out her slim, gloved hand to Hallett. But he was not inclined to let her escape so easily. She owed him something, if only an explanation.

‘I am going your way,’ he said, unblushingly. ‘Perhaps, if you don’t mind—’

Menzies stroked his moustache, and his eyes roved sideways to his aide-de-camp, Royal, who, after an absence of two or three minutes had now returned. Royal nodded almost imperceptibly, and the inspector said good-bye.

‘By the way, you had better be at the police court at two, Mr Hallett. We shall charge this man Smith today. I don’t expect you’ll be kept long. It will be purely formal. I shall apply for a remand.’

Hallett and the girl went down the steps to the street. He was conscious that, though she appeared to be gazing serenely in front of her, she occasionally scrutinised him with curious eyes.

Not till they were a hundred yards away from the police-station did either of them speak again. Then Jimmie ventured on the ice.

‘Perhaps now you will tell me what it’s all about?’

‘Oh!’ She stopped and turned full on him with wide-open, innocent blue eyes of a child. ‘So you knew all the time? I wasn’t sure.’

‘Wasn’t sure that I knew you as the girl in the fog?’

‘Yes. Shall we walk on? We might attract attention standing here. Why did you do it? Why didn’t you denounce me?’

Jimmie twiddled his walking-stick.

‘Hanged if I know!’ he confessed. Her self-possession rather daunted him. ‘I thought—that is—if you wanted to you would have explained the incident yourself.’

‘That’s no reason. You didn’t know me. There was no earthly motive. All the same, I am grateful to you, Mr Hallett—sincerely grateful.’

She sighed.

A porter with a parcel under his arm loitered three yards behind them. Ten yards behind him a ‘nut’, scrupulously dressed and seeming conscious of nothing but the beauty of his attire, swaggered aimlessly. Menzies, as has been said, was not a man who took anything for granted. His arrangements for ‘covering’ Peggy Greye-Stratton in the event of Hallett not recognising her had been completed long before he had confronted them in the charge-room.

Hallett might have guessed—if he had thought about it at all. The girl certainly did not. Jimmie caught at her last words.

‘You can prove that. Although we have only been formally introduced in the last five minutes, we are not exactly strangers. Come and lunch with me. Then we can talk. There are several things I want to know.’

She assented, it seemed to him, somewhat indifferently. He hailed a taxi-cab, and gave the name of a famous restaurant. As she sank back in the cushions it was as though a mask had dropped from her face. It had suddenly become utterly weary. She gasped once or twice as if for breath. Only for an instant had the mask dropped, but Hallett had seen and understood. The girl was strained to breaking-point, supporting her part only by strength of will.

What that part was, and why she was playing it, he was fixed in the resolution to learn. He spoke on indifferent subjects till lunch was over and coffee was brought. Then he leaned forward a little across the table.

‘I shall be glad if I can be of any help to you, Miss Greye-Stratton,’ he said.

A smile, palpably forced, appeared on the girl’s face. She twisted a ring on her finger absently.

‘That is a polite way of bringing me to the point, Mr Hallett. You have a sort of right to ask.’

A sigh trembled on her lips, and her eyes became absent. The man said nothing, but waited. Very dainty and desirable did Peggy Greye-Stratton seem to him then. Yet he would not have been human if he had not had misgivings. Her very reluctance to speak aroused a little spark of suspicion which he deliberately trampled under foot. A beautiful face, a high intelligence, and courage—and all these he knew she possessed—are not necessarily guarantees against crime.

She appeared to come to a resolve.

‘I will tell you what I told Mr Menzies,’ she said, looking up. ‘Knowing what you knew, it will seem incomplete to you, but you’—she looked him full in the face—‘are a gentleman. I trust you not to question me too far. There are—other people.’

He, too, had come to a resolve.

‘Tell me,’ he said levelly, ‘before you say anything else, did you have act or part in the murder of your father?’

She stared at him whitely and half rose. Her shapely throat was working strangely.

‘Do you think—’ she began. And then tensely: ‘No, no, no!’ Her voice fell to a strained whisper. ‘Why do you ask me that? If I had known—if I could have prevented—’

She was rapidly becoming distraught.

He felt himself a cur, but he pressed home the question relentlessly.

‘Do you know who it was that murdered your father?’

Her fair head fell to her arms on the table. Had Hallett known, he could not have put his questions at