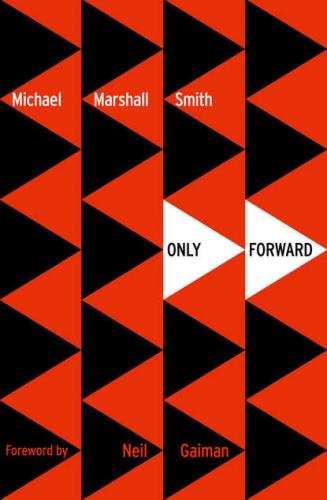

Only Forward. Michael Marshall Smith

sound wasn’t bothering me so much. But once I’ve made up my mind about something I stick to it, so off I went again.

It was a long and arduous journey, full of trials, setbacks and heroic derring-do on my part. I was almost there, for example, when I ran out of cigarettes, and had to go back to fetch another packet.

The phone was still ringing when I reached the other side, which was useful, because now I was there I had to find the damn thing. Half a year ago some client gave me a Gravbenda™ in part-payment for a job I’d done them. Maybe you’ve got one: what they do is let you alter the gravity in selected rooms in your apartment, change the direction, how heavy things are, that sort of stuff. So for a while I had the gravity in the living room going left to right instead of downwards. Kind of fun. Then the batteries ran out and everything just dropped in a pile down the far end of the room. And frankly, I couldn’t be fucked to do anything about it.

It took me a while to find the phone. The screen was cracked and the ringing sound was more of a warble than it used to be, though maybe it was just tired: it’d been ringing for over two hours by then. I pressed to receive and the screen flashed ‘Incoming Call’, blinked, and then showed a woman’s face. She looked pretty irritable, and also familiar.

‘Wow, Stark: have a tough time finding the phone, did you?’

I peered at the screen, trying to remember who it was. She was about my age, and very attractive.

‘Yes, as it happens. Who are you?’

The woman sighed heavily.

‘It’s Zenda, Stark. Get a grip.’

When I say I’m tired, you see, I don’t just mean that I’m tired. I have this disease. It’s nothing new: people have had it for centuries. You know when you’ve got nothing in particular to do, nothing to stay awake for? When your life is just routine and it doesn’t feel like it belongs to you, how you feel tired and listless and everything seems like too much effort?

Well it’s like that, but it’s much worse, because everything is much worse these days. Everything that’s bad is worse, believe me. Everything is accelerating, compacting and solidifying. There are whole Neighbourhoods out there where no one has had anything to do all their lives. They’re born, and from the moment they hit the table, there’s nothing to do. They clamber to their feet occasionally, realise there’s nothing to do, and sit down again. They grow up, and there’s nothing, they grow old and there’s still nothing. They spend their whole lives indoors, in armchairs, in bed, wondering who they are.

I grew up in a Neighbourhood like that, but I got out. I got a life. But when that life slows down, the disease creeps up real fast. You’ve got to keep on top of it.

‘Zenda, shit. I mean Hi. How are you?’

‘I’m fine. How are you?’

‘Pretty tired.’

‘I can tell. Look, I could have something for you here. How long would it take you to get dressed?’

‘I am dressed.’

‘Properly, Stark. For a meeting. How soon could you be down here?’

‘I don’t know. Two, three months?’

‘You‘ve got an hour.’

The screen went blank. She’s a characterful person, Zenda, and doesn’t take any shit. She’s my contact at Action Centre, the area where all the people who are into doing things hang out. It’s a whole Neighbourhood, with offices and buildings and shops and sub-sections, all totally dedicated and geared up for people who always have to be doing something. Competition to get in is pretty tough, obviously, because everyone is prepared to do what it takes, to get things done, to work, all the fucking time. A hundred per cent can-do mentality. Once you’re in you’ve got to work even harder, because there’s always somebody on the outside striving twenty-five hours a day to take your place.

They’re a pretty heavy bunch, the Actioneers: even when they’re asleep they’re on the phone and working out with weights, and most of them have had the need to sleep surgically removed anyway. For me, they’re difficult to take for more than a few seconds at a stretch. But Zenda’s okay. She’s only been there five years, and she’s lasted pretty well. I just wish she’d take some shit occasionally.

I found some proper clothes quite easily. They were in another room, one where I haven’t fucked about with the gravity. They were pretty screwed up, but I have a CloazValet™ that takes care of that, another part-payment. It somehow also changed the colour of the trousers from black to emerald with little turquoise diamonds, but I thought what the hell, start a trend.

The walls in the bedroom were bright orange, which meant it was about seven o’clock at night. It also meant I’d spent a whole day sitting with my back to the wall. I don’t think I’ll ever make it into the Centre, somehow.

Getting to Zenda’s building in Action Centre would take at least half an hour, probably more, even assuming I could find it. They keep moving the buildings around just for something to do in lunchbreaks, and if you don’t keep up with the pace you can walk into the Centre and not know where anything is. The Actioneers are always up with the pace, of course. I’m not.

I told the apartment to behave and got out onto the streets.

The fact that Zenda had asked me to change meant that I was almost certainly going to be meeting someone. I meet a lot of people. Some of them need what I can do for them, and don’t care what I look like: by the time I’m the only person who can help them, they’re prepared to put up with sartorial vagueness.

But most of them just want something minor fixed, and only like giving money to people who’ll dress up neatly for them. They insist on value. I hadn’t been able to tell from Zenda’s tone whether this was to be a special thing, or just a run-of-the-mill one, but the request for tidiness implied the latter.

All that stuff about the disease, by the way, it wasn’t true. Well it was, but it was an exaggeration. There are Neighbourhoods like I described, but I’m not from there. I’m not from anywhere, and that’s why I’m so good at what I do. I’m not stuck, I’m not fixed, and I don’t faze easily. To faze me you’d have to prove to me that I was someone else, and then I’d probably just ask to be properly introduced.

I was just tired. I’d had three hours’ sleep the night before, which I think you’ll agree isn’t much. I’m not asking for sympathy though: three hours is pretty good for me. In my terms, three hours makes me Rip van Winkle. I was tired because I’d only been back two days after my last job. I’ll tell you about it sometime, if it’s relevant.

The streets were pretty quiet, which was nice. They’re always quiet here at that time: you have to be wearing a black jacket to be out on the streets between seven and nine in the evening, and not many people in the area have black jackets. It’s just one of those things. I currently live in Colour Neighbourhood, which is for people who are heavily into colour. All the streets and buildings are set for instant colourmatch: as you walk down the road they change hue to offset whatever you’re wearing. When the streets are busy it’s kind of intense, and anyone prone to epileptic seizures isn’t allowed to live in the Neighbourhood, however much they’re into colour.

I’m not into colour that deeply myself, I just live here because it’s one of the milder weirdnesses in The City, one of the more relaxed Neighbourhoods. Also you can tell the time by the colour of the internal walls of the residential apartments, which is kind of useful as I hate watches.

The streets thought about it for a while, then decided that matt black was the ideal compliment for my outfit. Some of the streetlights were picked out in the same turquoise as the diamonds in my trousers too, which I thought was kind of a nice touch. I made a mental note to tell the next Street Engineer I met that they were doing a damn fine job. Sort of an embarrassing thing to think, but I knew I was safe: I always lose my mental notes.

Last time I’d ventured out of the apartment the monorail wasn’t working, but they’d obviously