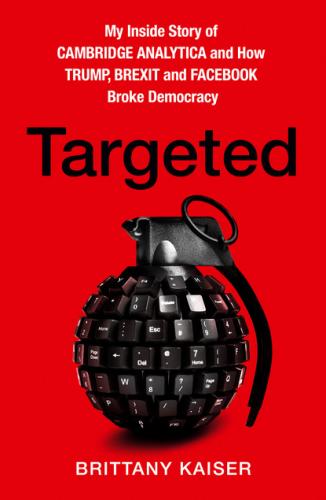

Targeted. Brittany Kaiser

was: someone who used data as a means to an end and who worked, it was clear, for many people in the United States whom I considered my opposition. I seemed to have dodged a bullet.

I thought Chester’s friends wouldn’t choose to work with Nix. His presence and presentation were too large and extravagant, too big for them and for the room. His ebullience had been charming and persuasive; he had even tempered his immodesty with exquisitely honed British manners, but his bluster and ambition were out of proportion with their needs. Nix, though, seemed oblivious to the men’s reserve. As he packed up to leave the restaurant, he prattled on about how he could help them with specially segmented audiences.

When Nix got up from the table, I realized I’d still have time to pitch Chester’s friends. Once Nix was out the door, I intended to approach them now privately, with a simple and modest proposal. But as Nix began to go, Chester gestured to me that I ought to join him in saying a proper good-bye.

Outside in the cold, with the afternoon light waning, Chester and I stood with Nix in a few long seconds of awkward silence. But for as long as I had known him, Chester had never been able to tolerate silence of any length.

“Hey, my Democrat consultant friend, you should hang out with my Republican consultant friend!” he blurted out.

Nix flashed Chester a sudden and strange look, a combination of alarm and annoyance. He clearly didn’t like being caught off guard or told what to do. Still, he reached into his suit coat pocket and pulled out a messy stack of business cards and began shuffling through them. The cards he’d taken out clearly weren’t his. They were of varied sizes and colors, likely from businessmen and potential clients like Chester’s visiting friends, other men to whom he must have pitched his wares on similar Mayfair afternoons.

Finally, when he fished out one of his own cards, he handed it to me with a flourish, waiting while I paused to take it in.

“Alexander James Ashburner Nix,” the card read. From the weight of the paper stock on which it was printed to its serif typeface, it screamed royalty.

“Let me get you drunk and steal your secrets,” Alexander Nix said, and laughed, but I could tell he was only half joking.

OCTOBER–DECEMBER 2014

In the months after I first met Alexander Nix, I still wasn’t able to secure any work that would substantially improve my family’s current financial situation. In October 2014, I reached out again to Chester for help in finding the right kind of part-time job, and he responded by arranging a meeting for me with his prime minister.

It was a rare opportunity for me to offer digital and social media strategy to a nation’s leader. The prime minister was a multiterm incumbent running for reelection, but this time he was facing strong opposition in his country and was concerned about losing. Chester wanted to introduce me to him to see how I might be of help.

This was how, quite inadvertently, I ran into Alexander Nix a second time.

I was in the lounge of a private jet hangar at Gatwick Airport, waiting for a morning meeting with the prime minister, when the door of the lounge flew open and Nix burst in. I was early for my meeting; his was the first one of the day, and of course it had to have been scheduled before mine. My poor luck again.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, his expression both threatening and threatened. He clutched his beaten-up briefcase to his chest and leaned backward in mock horror. “Are you stalking me?”

I laughed.

When I told him what I was doing there, he let me know that he had been working with the prime minister on the past few elections. He was fascinated to hear that I was there “hoping” to do the same thing.

We exchanged some small talk. And when he was called in to his meeting, he tossed an invitation over his shoulder. “You should come to the SCL office sometime and learn more about what we do,” he said, and then he was gone.

Although I was still wary of him, I would indeed choose to visit Alexander Nix at the SCL office. A few days after our chance encounter at Gatwick, Chester called to say that “Alexander” had been in touch, and could the three of us get together and perhaps chat about what we all might be thinking about the prime minister’s upcoming election?

I found myself strangely and pleasantly surprised at the idea. Something about running into me at the hangar must have caught Alexander’s attention. Perhaps he wasn’t used to boldness in someone of my age and gender. Whatever his reason, the proposed meeting was about working together, which struck me as far more positive than working against each other, given that he obviously had the upper hand and especially because I truly needed work.

In mid-October, Chester and I visited the SCL office together. It was tucked away off Green Park, near Shepherd Market, down an alley and off a road called Yarmouth Place, and it occupied a worn-looking building that appeared not to have been rehabbed since the 1960s. The building was filled with offices of unknown small start-ups, such as the drinkable-vitamins company SCL shared a hallway with. Wooden crates filled with tiny bottles nearly blocked our way into the ground-floor conference room, which was shared among all tenants and needed to be rented by the hour—not exactly what I expected of such a seemingly-posh crew of political consultants.

But it was that room where Chester and I met with Alexander and Kieran Ward, whom Alexander introduced to us as his director of communications. Alexander said Kieran had been on the ground for SCL in many foreign elections; he appeared to be only in his mid-thirties, but the expression in his eyes told me they had seen a lot.

There was a great deal at stake in the election of the prime minister, Alexander told us. The PM had “an inflated ego,” he said. Chester nodded in assent. This was the PM’s fifth bid for office, and amid dissatisfaction, his people were calling for him to step down. In his meeting with him at Gatwick, Alexander had warned the PM that if he “didn’t batten down the hatches,” he was certain to lose, but there was little time left. The election was coming up in a few months, after the turn of the New Year.

What SCL was hoping to do, Alexander began, and then he stopped himself. He looked at Chester and me. “But you don’t even know what we do, do you?” and before we knew it, he’d slipped out the door and slipped back in again, laptop in hand. He turned down the lights and pulled up a PowerPoint presentation that he projected onto a big screen on the wall.

“Our children,” he began, clicker in hand, “won’t live in a world with ‘blanket advertising,’” he said, referring to the messaging intended for a broad audience and sent out in a giant, homogenous blast. “Blanket advertising is just too imprecise.”

He pulled up a slide that read, “Traditional Advertising Builds Brands and Provides Social Proof but Doesn’t Change Behavior.” On the left-hand side of the slide was an advertisement for Harrods department store that read 50% OFF SALE in large type. On the right were the McDonald’s and Burger King logos, arches and a crown.

These kinds of ads, he explained, either were simply informational or, if they even worked, merely “proved” an existing customer’s loyalty to a brand. The approach was antiquated.

“The SCL Group offers messaging built for a twenty-first-century world,” Alexander said. Traditional marketing like these ads would never work.

If a client wanted to reach new customers, “What you have to do,” he explained, was not just reach them but “convert” them. “How can McDonald’s get somebody to eat one of their burgers when they’ve never done so before?”

He shrugged and clicked to the next slide.

“The Holy Grail of communications,” he said, “is when you can actually start to change behavior.”

The next slide