Beyond Black. Hilary Mantel

woke up on the day, she had an urge to run downstairs, and howl in the streets of Whitton. Instead, she pressed her frock and climbed into it. She was alone in the flat; Gavin was on his stag night, and she wondered what she would do if he didn’t turn up; marry herself? The wedding was designed to be exhausting, to wring value from each moment they had paid for. So they could recover, she had booked ten days in the Seychelles: sea view, balcony, private taxi transfer and fruit in room on arrival.

Gavin turned up just in time, his eyes pouched and his skin grey. After the registry, they went out to a hotel in Berkshire with a trout stream running through the grounds and fishing flies in glass cases on the walls of the bar, and French windows leading on to a terrace. She was photographed against the stone balustrade, with Gavin’s little nieces pawing her skirts. They had a marquee, and a band. They had gravadlax with dill sauce, served on black plates, and a chicken dish which tasted, Gavin said, like an airline dinner. The Uxbridge people on both sides came, and never spoke to each other. Gavin kept belching. A niece was sick, luckily not on Colette’s dress, which was hired. Her tiara, though, was bought: a special order to fit her narrow skull. Later she didn’t know what to do with it. Space was tight in the flat in Whitton, and her drawers were crammed with packets of tights, which she bought by the dozen, and with sachets and scent balls to perfume her knickers. When she reached in among her underwear, the faux pearls of the tiara would roll beneath her fingers, and its gilt lattices and scrolls would remind her that her life was open, unfolding. It seemed mercenary to advertise it in the local paper. Besides, Gavin said, there can’t be two people with a head shaped like yours.

The pudding at their wedding breakfast was strawberries and meringue stacked up in a tower, served on frosted-glass platters sprinkled with little green flecks, which proved to be not chopped mint leaves but finely snipped chives. Uxbridge ate it with a stout appetite; after all, they’d already done raw fish. But Colette – once her suspicion was verified, by a tiny taste at the tip of her tongue – had flown out, in her tiara, cornered the duty manager, and told him she proposed to sue the hotel in the small claims court. They paid her off, as she knew they would, being afraid of the publicity; she and Gavin went back there gratis, for their anniversary dinner, and enjoyed a bottle of house champagne. It was too wet that night to walk by the trout stream: a lowering, misty evening in June. Gavin said it was too hot, and walked out on to the terrace as she was finishing her main course. By then the marriage was over, anyway.

It was no particular sexual incompatibility that had broken up her marriage: Gavin liked it on Sunday mornings, and she had no objection. Neither was there, as she learned later, any particular planetary incompatibility. It was just that the time had come in her relationship with Gavin when, as people said, ‘she could see no future in it’.

When she arrived at this point, she bought a large-format softback called What Your Handwriting Reveals. She was disappointed to find that your handwriting can’t shed any light on your future. It only tells of character, and your present and your past, and her present and her past she was clear about. As for her character, she didn’t seem to have any. It was because of her character that she was reduced to going to bookshops.

The following week she returned the handwriting book to the shop. They were having a promotional offer, bring it back if it doesn’t thrill. She had to tell the boy behind the counter why, exactly, it didn’t; I suppose, she said, after so many years of word processing, I have no handwriting left. Her eyes flickered over him, from his head downwards, to where the counter cut off the view; she was already, she realised, looking for a man she could move on to. ‘Can I see the manager?’ she asked, and amiably, scratching his barnet, the boy replied, ‘You’re looking at him.’

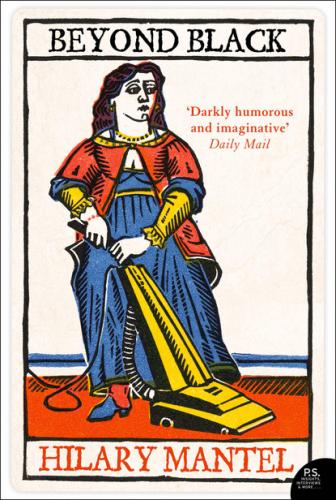

‘Really?’ she said. She had never seen it before: a manager who dressed out of a skip. He gave her back her money, and she browsed the shelves, and picked up a book about tarot cards. ‘You’ll need a pack to go with that,’ the boy said, when she got to the cash desk. ‘Otherwise you won’t get the idea. There are different sorts, shall I show you? There’s Egyptian tarot. There’s Shakespeare tarot. Do you like Shakespeare?’

As if, she thought. She was the last customer of the evening. He closed up the shop and they went to the pub. He had a room in a shared flat. In bed he kept pressing her clit with his finger, as if he were inputting a sale on the cash machine: saying, Helen, is that all right for you? She’d given him a wrong name, and she hated it, that he couldn’t see through to what she was really called. She’d thought Gavin was useless: but honestly! In the end she faked it, because she was bored and she was getting cramp. The Shakespeare boy said, Helen, that was great for me too.

It was the tarot that started her off. Before that she had been just like everybody, reading her horoscope in the morning paper. She wouldn’t have described herself as superstitious or interested in the occult in any way. The next book she bought – from a different bookshop – was An Encyclopedia of the Psychic Arts. ‘Occult’, she discovered, meant hidden. She was beginning to feel that everything of interest was hidden. And none of it in the obvious places; don’t, for example, look in trousers.

She had left that original tarot pack in the boy’s room, inadvertently. She wondered if he had ever taken it out and looked at the pictures; whether he ever thought of her, a mysterious stranger, a passing Queen of Hearts. She thought of buying another set, but what she read in the handbook baffled and bored her. Seventy-eight cards! Better employ someone qualified to read them for you. She began to visit a woman in Isleworth, but it turned out that her speciality was the crystal ball. The object sat between them on a black velvet cloth; she had expected it to be clear, because that’s what they said, crystal clear, but to look into it was like looking into a cloud bank, or into drifting fog. ‘The clear ones are glass, dear,’ the sensitive explained. ‘You won’t get anything from those.’ She rested her veined hands on the black velvet. ‘It’s the flaws that are vital,’ she said. ‘The flaws are what you pay for. You will find some readers who prefer the black mirror. That is an option, of course.’ Colette raised her eyebrows.

‘Onyx,’ the woman said. ‘The best are beyond price. The more you look – but you have to know how to look – the more you see stirring in the depths.’

Colette asked straight out, and heard that her crystal ball had set her back five hundred pounds. ‘And then only because I have a special friend.’ The psychic gained, in Colette’s eyes, a deal of prestige. She was avid to part with her twenty pounds for the reading. She drunk in everything the woman said, and when she hit the Isleworth pavement, moss growing between its cracks, she was unable to remember a word of it.

She consulted a palmist a few times, and had her horoscope cast. Then she had Gavin’s done. She wasn’t sure that his chart was valid, because she couldn’t specify the time of his birth. ‘What do you want to know that for?’ he’d said, when she asked him. She said it was of general interest to her, and he glared at her with extreme suspicion.

‘I suppose you don’t know, do you?’ she said. ‘I could ring your mum.’

‘I very much doubt,’ he’d said, ‘that my mother would have retained that piece of useless information, her brain being somewhat overburdened in my opinion with things like where is my plastic washball for my Persil, and what is the latest development in bloody EastEnders.’

The astrologer was unfazed by her ignorance. ‘Round it up,’ he said, ‘round it down. Twelve noon is what we use. We always do it for animals.’

‘For animals?’ she’d said. ‘They have their horoscope done, do they?’

‘Oh, certainly. It’s a valuable service, you see, for the caring owner who has a problem with a pet. Imagine, for instance, if you kept falling off your horse. You’d need to know, is this an ideal pairing? It could be a matter of life or death.’

‘And do people know when their horse was born?’

‘Frankly, no. That’s why we have a strategy to approximate. And as for your partner – if we say noon, that’s fine, but we then need latitude and longitude – so where do we imagine hubby first saw the light of day?’

Colette sniffed. ‘He won’t say.’