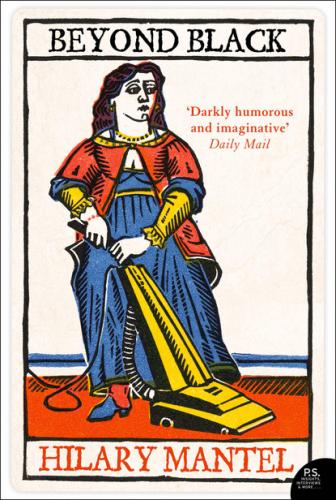

Beyond Black. Hilary Mantel

about for you: cards, crystal and psychometry thrown in, thirty quid.

Alison blushed, a deep crimson blush. ‘She said that? Thirty quid?’

‘Fancy you not knowing.’

‘My mind was somewhere else.’ She laughed shakily. ‘Voilà. You’ve already earned your money, Colette.’

‘You know my name?’

‘It’s that certain something French about you. Je ne sais quoi.’

‘You speak French?’

‘Never till today.’

‘You mustn’t mind-read me.’

‘I would try not to.’

‘An hour and a quarter?’

‘You could get some fresh air.’

On Windsor Bridge, a young boy was sitting on a bench with his Rottweiler at his feet. He was eating an ice-cream cone and holding another out to the dog. Passers-by, smiling, were collecting to watch. The dog ate with civil, swirling motions of his tongue. Then he crunched the last of his cornet, swarmed up on to the bench and laid his head lovingly on the boy’s shoulder. The boy fed him the last of his own ice cream, and the crowd laughed. The dog, encouraged, licked and nibbled the boy’s ears, and the crowd went ohh, feech, yuk, how sweet.

The dog jumped down from the bench. Its eyes were steady and its paws huge. For two pins, or the dog equivalent, it would set itself to eat the crowd, worrying each nape and tossing the children like pancakes.

Colette stood and watched until all the crowd had dispersed and she was alone. She crossed the bridge and edged down Eton High Street, impeded by tourists. I am like the dog, she thought. I have an appetite. Is that wrong? My mum had an appetite. I realise it now, how she talked in code all those years. No wonder I never knew what was what and who was who. Not surprising her aunts were always exchanging glances, and saying things like, I wonder where Colette gets her hair from, I wonder where she gets her brains? The man she’d called her father was distinguished by the sort of stupidity that made him squalid. She had a mental picture of him, sprawled before the television scratching his belly: perhaps, when she’d bought him the cuff-links, she’d been hoping to improve him. Her uncle Mike, on the other hand – who was really her father – he was a man whose wallet was always stuffed, hadn’t he been round every week, flashing his fivers and saying, here, Angie, get something nice for little Colette? He’d paid, but he hadn’t paid enough; he’d paid as an uncle, but not as a dad. I’ll sue the bastard, she thought. Then she remembered he was dead.

She went into the Crown & Cushion and got a pineapple juice, which she took into a corner. Every few minutes she checked her watch. Too early, she started back across the bridge.

Alison was sitting in the front room of the Harte & Garter with a cafetière and two cups. She had her back to the door, and Colette paused for a moment, getting a view of her: she’s huge, she thought, how can she go around like that? As she watched, Alison’s plump smooth arm reached for the coffee and poured it into the second cup.

Colette sat down. She crossed her legs. She fixed Alison with a cool stare. ‘You don’t mind what you say, do you? You could have really upset me, back there.’

‘There was a risk.’ Alison smiled.

‘You think you’re a good judge of character.’

‘More often than not.’

‘And my mum. I mean, for all you know, I could have burst into tears, I could have collapsed.’

Not a real risk, Al thought. At some level, in some recess of themselves, people know what they know. But the client was determined to have her moment.

‘Because what you were saying, really, is that she was having an affair with my uncle under my dad’s nose. Which isn’t nice, is it? And she let my dad think I was his.’

‘I wouldn’t call it an affair. It was more of a fling.’

‘So what does that make her? A slag.’

Alison put down her coffee cup. ‘They say don’t speak ill of the dead.’ She laughed. ‘But why not? They speak ill of you.’

‘Do they?’ Colette thought of Renee. ‘What are they saying?’

‘A joke. I was making a joke. I see you think I shouldn’t.’

She took from Colette the thimble-sized carton of milk she was fumbling with, flicked up the foil with her nail, tipped the milk into Colette’s coffee.

‘Black. I take it black.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Another thing you didn’t know.’

‘Another.’

‘This job you were talking about – ’ Colette broke off. She narrowed her eyes, and looked speculatively at Al, as if she were a long way off.

Al said, ‘Don’t frown. You’ll stay like that one day. Just ask me what you need to ask.’

‘Don’t you know?’

‘You asked me not to read your mind.’

‘You’re right. I did. Fair’s fair. But can you shut it off like that? Shut it off and then just turn it on when you want it?’

‘It’s not like that. I don’t know how I can explain. It’s not like a tap.’

‘Is it like a switch?’

‘Not like a switch.’

‘It’s like – I suppose – is it like somebody whispering to you?’

‘Yes. More like that. But not exactly whispering. I mean, not in your ear.’

‘Not in your ear.’ Colette stirred her coffee. Al picked up a paper straw of brown sugar, pinched off the end and dropped it into Colette’s cup. ‘You need the energy,’ she explained. Colette, frowning, continued to stir.

‘I have to get back soon,’ Al said. ‘They’re building up in there.’

‘So if it’s not a switch – ’

‘About the job – you could sleep on it.’

‘And it’s not a tap – ’

‘You could ring me tomorrow.’

‘And it’s not somebody whispering in your ear – ’

‘My number’s on the leaflet. Have you got my leaflet?’

‘Does your spirit guide tell you things?’

‘Don’t leave it too long.’

‘You said he was called Morris. A little bouncing circus clown.’

‘Yes.’

‘Sounds a pain.’

‘He can be. ’

‘Does he live with you? In your house? I mean, if you call it “live”?’

‘You might as well,’ Al said. She sounded tired. ‘You might as well call it “live”, as call it anything.’ She pushed herself to her feet. ‘It’s going to be a long afternoon.’

‘Where do you live?’

‘Wexham.’

‘Is that far?’

‘Just up into Bucks.’

‘How do you get home, do you drive?’

‘Train and then a taxi.’

‘By the way, I think you must be right. About my family.’

Al looked down at her. ‘I sense you’re wavering. I mean, about my