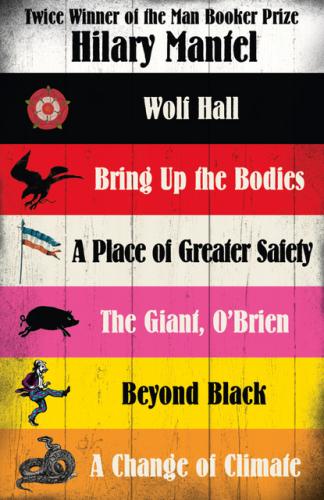

Hilary Mantel Collection. Hilary Mantel

all outcomes can be managed, even massaged into desirability: prayer and pressure, pressure and prayer, everything that comes to pass will pass by God's design, a design re-envisaged and redrawn, with helpful emendations, by the cardinal. He used to say, ‘The king will do such-and-such.’ Then he began to say, ‘We will do such-and-such.’ Now he says, ‘This is what I will do.’

‘But what will happen to the queen?’ he asks. ‘If he casts her off, where will she go?’

‘Convents can be comfortable.’

‘Perhaps she will go home to Spain.’

‘No, I think not. It is another country now. It is – what? – twenty-seven years since she landed in England.’ The cardinal sighs. ‘I remember her, at her coming-in. Her ships, as you know, had been delayed by the weather, and she had been day upon day tossed in the Channel. The old king rode down the country, determined to meet her. She was then at Dogmersfield, at the Bishop of Bath's palace, and making slow progress towards London; it was November and, yes, it was raining. At his arriving, her household stood upon their Spanish manners: the princess must remained veiled, until her husband sees her on her wedding day. But you know the old king!’

He did not, of course; he was born on or about the date the old king, a renegade and a refugee all his life, fought his way to an unlikely throne. Wolsey talks as if he himself had witnessed everything, eye-witnessed it, and in a sense he has, for the recent past arranges itself only in the patterns acknowledged by his superior mind, and agreeable to his eye. He smiles. ‘The old king, in his later years, the least thing could arouse his suspicion. He made some show of reining back to confer with his escort, and then he leapt – he was still a lean man – from the saddle, and told the Spanish to their faces, he would see her or else. My land and my laws, he said; we'll have no veils here. Why may I not see her, have I been cheated, is she deformed, is it that you are proposing to marry my son Arthur to a monster?’

Thomas thinks, he was being unnecessarily Welsh.

‘Meanwhile her women had put the little creature into bed; or said they had, for they thought that in bed she would be safe against him. Not a bit. King Henry strode through the rooms, looking as if he had in mind to tear back the bedclothes. The women bundled her into some decency. He burst into the chamber. At the sight of her, he forgot his Latin. He stammered and backed out like a tongue-tied boy.’ The cardinal chuckled. ‘And then when she first danced at court – our poor prince Arthur sat smiling on the dais, but the little girl could hardly sit still in her chair – no one knew the Spanish dances, so she took to the floor with one of her ladies. I will never forget that turn of her head, that moment when her beautiful red hair slid over one shoulder … There was no man who saw it who didn't imagine – though the dance was in fact very sedate … Ah dear. She was sixteen.’

The cardinal looks into space and Thomas says, ‘God forgive you?’

‘God forgive us all. The old king was constantly taking his lust to confession. Prince Arthur died, then soon after the queen died, and when the old king found himself a widower he thought he might marry Katherine himself. But then …’ He lifts his princely shoulders. ‘They couldn't agree over the dowry, you know. The old fox, Ferdinand, her father. He would fox you out of any payment due. But our present Majesty was a boy of ten when he danced at his brother's wedding, and, in my belief, it was there and then that he set his heart on the bride.’

They sit and think for a bit. It's sad, they both know it's sad. The old king freezing her out, keeping her in the kingdom and keeping her poor, unwilling to miss the part of the dowry he said was still owing, and equally unwilling to pay her widow's portion and let her go. But then it's interesting too, the extensive diplomatic contacts the little girl picked up during those years, the expertise in playing off one interest against another. When Henry married her he was eighteen, guileless. His father was no sooner dead than he claimed Katherine for his own. She was older than he was, and years of anxiety had sobered her and taken something from her looks. But the real woman was less vivid than the vision in his mind; he was greedy for what his older brother had owned. He felt again the little tremor of her hand, as she had rested it on his arm when he was a boy of ten. It was as if she had trusted him, as if – he told his intimates – she had recognised that she was never meant to be Arthur's wife, except in name; her body was reserved for him, the second son, upon whom she turned her beautiful blue-grey eyes, her compliant smile. She always loved me, the king would say. Seven years or so of diplomacy, if you can call it that, kept me from her side. But now I need fear no one. Rome has dispensed. The papers are in order. The alliances are set in place. I have married a virgin, since my poor brother did not touch her; I have married an alliance, her Spanish relatives; but, above all, I have married for love.

And now? Gone. Or as good as gone: half a lifetime waiting to be expunged, eased from the record.

‘Ah, well,’ the cardinal says. ‘What will be the outcome? The king expects his own way, but she, she will be hard to move.’

There is another story about Katherine, a different story. Henry went to France to have a little war; he left Katherine as regent. Down came the Scots; they were well beaten, and at Flodden the head of their king cut off. It was Katherine, that pink-and-white angel, who proposed to send the head in a bag by the first crossing, to cheer up her husband in his camp. They dissuaded her; told her it was, as a gesture, un-English. She sent, instead, a letter. And with it, the surcoat in which the Scottish king had died, which was stiffened, black and crackling with his pumped-out blood.

The fire dies, an ashy log subsiding; the cardinal, wrapped in his dreams, rises from his chair and personally kicks it. He stands looking down, twisting the rings on his fingers, lost in thought. He shakes himself and says, ‘Long day. Go home. Don't dream of Yorkshiremen.’

Thomas Cromwell is now a little over forty years old. He is a man of strong build, not tall. Various expressions are available to his face, and one is readable: an expression of stifled amusement. His hair is dark, heavy and waving, and his small eyes, which are of very strong sight, light up in conversation: so the Spanish ambassador will tell us, quite soon. It is said he knows by heart the entire New Testament in Latin, and so as a servant of the cardinal is apt – ready with a text if abbots flounder. His speech is low and rapid, his manner assured; he is at home in courtroom or waterfront, bishop's palace or inn yard. He can draft a contract, train a falcon, draw a map, stop a street fight, furnish a house and fix a jury. He will quote you a nice point in the old authors, from Plato to Plautus and back again. He knows new poetry, and can say it in Italian. He works all hours, first up and last to bed. He makes money and he spends it. He will take a bet on anything.

He rises to leave, says, ‘If you did have a word with God and the sun came out, then the king could ride out with his gentlemen, and if he were not so fretted and confined then his spirits would rise, and he might not be thinking about Leviticus, and your life would be easier.’

‘You only partly understand him. He enjoys theology, almost as much as he enjoys riding out.’

He is at the door. Wolsey says, ‘By the way, the talk at court … His Grace the Duke of Norfolk is complaining that I have raised an evil spirit, and directed it to follow him about. If anyone mentions it to you … just deny it.’

He stands in the doorway, smiling slowly. The cardinal smiles too, as if to say, I have saved the good wine till last. Don't I know how to make you happy? Then the cardinal drops his head over his papers. He is a man who, in England's service, scarcely needs to sleep; four hours will refresh him, and he will be up when Westminster's bells have rung in another wet, smoky, lightless April day. ‘Good night,’ he says. ‘God bless you, Tom.’

Outside his people are waiting with lights to take him home. He has a house in Stepney but tonight he is going to his town house. A hand on his arm: Rafe Sadler, a slight young man with pale eyes. ‘How was Yorkshire?’

Rafe's smile flickers, the wind pulls the torch flame into a rainy blur.

‘I haven't to speak of it; the cardinal fears it will give us bad dreams.’

Rafe frowns. In all his twenty-one years he has never had bad dreams; sleeping securely