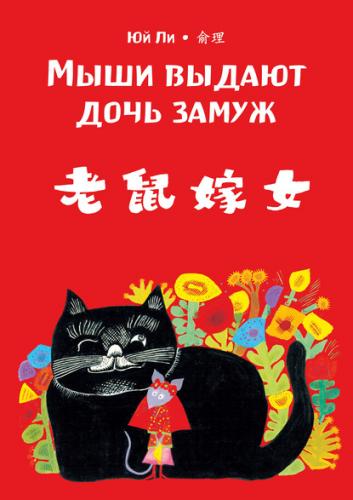

Мыши выдают дочь замуж. Народное творчество

ten o’clock Sunday morning. She lived only blocks away from his brownstone in Brooklyn.

His mother was standing at the stove in her kitchen. As she did every Sunday morning, the five-foot-two compact powerhouse of a woman was making pancakes. She had on a purple velour sweat suit, elaborate makeup, and her head was still swathed from the night before in the toilet paper turban that preserved the bouffant, flipped-at-the-ends hairdo sported by every woman who went to the neighborhood salon.

“Will you take that stuff off your head?” Michael added after he’d leaned over to kiss his mother’s cheek.

Elsa Dunnigan slid golden brown pancakes from the griddle, ladled more batter onto the hot surface, and then obliged her son by unwrapping her black hair. With the exception of being slightly flat in the back it remained an undisturbed helmet.

“The date, Mikey. I want to hear about the date.”

Michael picked up the already poured glass of orange juice at his spot at the red-and-silver kitchen table and took a drink, noting as he did that there were only two place settings. Unless Michael was working, Sunday breakfast was the one meal each week that he, his mother and his younger sister always tried to have together. So again he ignored his mother’s query in favor of one of his own.

“Cindy isn’t eating with us?”

“She had to go to a bridal shower brunch in the city,” Elsa said as if the entire subject of her other child was inconsequential. But as she took a platter filled with bacon and sausages from where it was being kept warm in the oven and brought that, a dish of pancakes and another plate of fried eggs to the table, she said, “And if you don’t answer me right now I’m going to call Dr. Miranda myself and tell her you had such a fabulous time with her last night that you want to see her again tonight.”

Michael knew his mother would do just that so he stopped hedging as they both sat at the table. “The date was good and bad—the bad being the date itself and the good being that it made me realize something and take a big step.”

He’d planned this out on the way home from Josie Tate’s apartment the previous night so he knew exactly how he was going to explain the sudden turn of events.

“I don’t understand,” his mother said. “You didn’t like Dr. Miranda?”

“No, Ma.”

Elsa Dunnigan frowned at him so fiercely it made her eyes squint and nearly disappear in the lines around them.

“She’s a nice girl,” his mother insisted. “A professional woman with a thriving medical practice. She wants to get married. She wants babies. She’ll make a good wife. She can’t help it if she has sinus problems and has to blow her nose every five minutes. And those ears could be covered if she’d just let her hair grow over them. I could set her up with Cissy—now that I’ve finally smoothed the waters after you never called her back, either. Cissy could do Dr. Miranda’s hair so no one would ever see those Dumbo ears.”

Cissy was Elsa’s beautician. She wore her hair even bigger and more rock-solid than any of her clients. Michael had spent the whole blind date with her wondering how she could not notice that the style was outdated by at least twenty years. And when he coupled the hair with the nearly Geisha-like makeup, the gum popping, the honking laugh, the dagger fingernails she’d used in lieu of a fork to pick up strands of spaghetti, and the fact that they’d had absolutely nothing in common, it had not been a date he’d wanted to repeat. So he hadn’t called her again. Much to his mother’s dismay.

But actually, just the thought of that date and the date the night before pushed him to finally tell his mother the story he’d come up with to free himself from any future setups.

“I’m engaged,” he announced.

Elsa made a very unflattering sound in response. Something like “Puh!”

Clearly she didn’t believe him.

“To Dr. Miranda?” she asked facetiously.

“No, not to Miranda. I told you I didn’t like her so you’re out of luck when it comes to free callus scrapings,” Michael informed her.

“Then who are you engaged to? As if I’m buying this load of horse manure.”

“Get out your checkbook because it’s true. I am engaged,” he said, enunciating each word slowly, as if to better get it to sink in.

“To who?” his mother said the same way.

“You don’t know her,” Michael answered calmly. He knew this was risky business. He’d never been an adept liar. And his mother had always been able to see through it when he’d tried. But now he had enough at stake to make him determined to pull it off. “Her name is Josie Tate. She’s the receptionist at that Manhattan Multiples place—remember, it was written up in the newspapers a few months ago? They help women who are pregnant with more than one baby or something. You showed me the article yourself—”

“I remember. My friend Agnes’s daughter went there when she was going to have triplets,” Elsa said, conceding that she knew what he was talking about but still sounding suspicious of his claim to be engaged.

“Well, Josie works there. We met the Friday night before Labor Day.”

“That was the night I arranged a date with my insurance agent’s secretary,” Elsa said to let him know he wasn’t putting anything over on her.

“Yes and Sharon McKinty is one of Josie’s roommates. She took me to a bar that night where Josie was reading poetry—poetry she wrote herself.”

It wasn’t easy to come up with a whole lot of information about his new fiancée because Michael didn’t know much about her. He was just trying to sound knowledgeable with what little he had learned over Labor Day weekend.

“You went out with Sharon McKinty and ended up with someone else?” his mother asked.

As a matter of fact.

“Sharon McKinty met up with an old boyfriend and deserted me. I told you that. But I stuck around to hear more of Josie’s poetry and when she was finished we…well, we hit it off.”

That was all true. Although to say that he and Josie Tate had hit it off was something of an under-statement.

“You told me Sharon dumped you,” his mother confirmed. “But you didn’t tell me you’d met someone else.” More suspicion.

“I wanted to keep this one to myself,” he said, as if Josie had just been too good to share when in fact meeting somebody in a bar and spending three days in bed with them was hardly a story to tell your mother. Even if it had been the best three days he’d ever spent. With anyone.

But despite Michael’s best attempt to make keeping Josie a secret sound romantic, his mother said, “Why did you want to keep it to yourself? Is there something wrong with her? Won’t I like her?”

“I wanted to keep her to myself because she’s just very special.”

That was no lie. Josie Tate did seem special. Special enough that after their weekend together he’d thought that to see her again could be too great a test of the vow he’d made to himself.

Michael had only told his mother once why he was resistant to her greatest desire—that he find a wife and have a family. Elsa had discounted it as silly and promptly disregarded it, but his reasons were strong nevertheless.

As a volunteer firefighter, his father had been killed in a burning building when Michael was only twelve. Being left without a dad had been tougher on him than he’d ever let his mother know. And then, when the World Trade Center bombings had happened and so many of his brother firefighters had been lost, when he’d seen so many wives, so many children, left behind, Michael had decided that if he was going to do this job he loved, he was not going to chance leaving behind a wife or a child.

Whether his mother liked it or not.

And