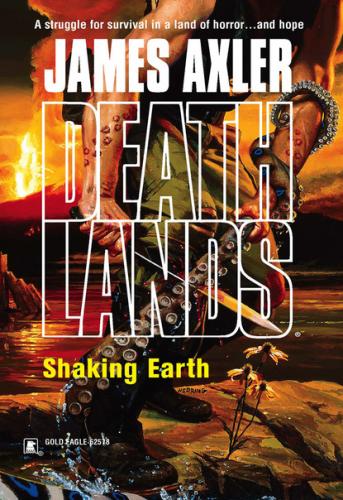

Shaking Earth. James Axler

with the blood of sacrificial victims glistening on his cheeks in the firelight, few could doubt the truth of what he said.

But Raven was among those few.

The boy’s father, Two Whirlwinds, had never recovered from the shock of seeing what he had sired. Despite the people’s judgment that the child was holy, he had felt shamed, tainted himself. He had begun to drink too much maguey wine, and when the child was two summers old had been surprised, dismembered and devoured by a pack of giant javelinas. Raven, elder brother to the boy’s mother, had assumed the role of father. It was a role he welcomed. From the very first, it seemed, there had been a special bond between the two. It took no mystic power to make him love the child as if he were his own.

And so, though he was little given to fruitless questioning, he wondered.

If it were all true, if the boy had been sent by forgotten gods to restore to the people their ancient glory—a glory that not even the eldest of the people had witnessed, nor even heard tales of, but that Howling Wolf assured them was their birthright—why hadn’t Raven, who raised the boy as a father, known of it before the strange priest came?

Chapter One

Long white hair streaming behind him, the young man ran through the woods. On the matlike floor of dead needles his combat moccasin boots made little more sound than morning mist flowing between the straight boles of spruce and fir. He was short and slight of build, and expertly dodged around potentially noisy patches of scrub oak, dry-leaved and prone to rattle in the early spring, nor did he brush against low-hanging tree boughs. Yet the fact he moved so quietly, despite the fact he ran flat-out, and even when he vaulted a low snaggle-toothed arch of dead fallen tree, seemed somehow almost supernatural.

That the skin of his face was as white as his hair did nothing to dispel the ghostly illusion. Nor did his eyes, narrowed with exertion, that gleamed red as shards of ruby. But ectoplasm wouldn’t take scars like the ones that seamed his narrow feral face and pulled the right-hand corner of his mouth upward in a hint of perpetual grin. Nor was there anything the least bit insubstantial about the chrome-plated steel of the .357 Magnum Colt Python blaster he clutched in his right hand.

As swift as a deer he moved and as silent as a thought. But his hunter’s heart, virtual stranger to fear, felt it now. Because as fast as he was, he was whipped by the dread certainty he couldn’t move fast enough to save his friends.

“THE BOY STOOD on the burning deck,” the gaunt old man declaimed in a voice of brass.

“How come,” asked the stocky black woman clad in an olive-drab T-shirt and baggy camou pants, “I’m the one who usually winds up elbow-deep in deer guts whenever we get lucky hunting?”

J. B. Dix, known otherwise as the Armorer, grinned at her around the carcass of the young whitetail buck that had been strung from a sturdy tree limb by its hind legs. Morning sunlight glinted off the round lenses of his steel-framed spectacles. “’Cause you’re the doctor, Millie. You wield a mean scalpel.”

She flipped him a gory bird.

“The boy stood on the burning deck,” the old man said, even more loudly. He had the air of a man trying to jar something loose from memory’s grasp. He was tall, with lank gray-white hair that fell to his shoulders. He wore a calf-length frock coat that had seen better days and cradled a Smith & Wesson M-4000 shotgun in his twig-skinny arms.

“I was a cryogenics researcher, for God’s sake, John, not a surgeon,” the black woman said. “Much less a veterinary pathologist.”

J.B. smiled. “Well, I reckon you know what you’re doing.”

“You might as well make that crazy old coot you’re trusting with your shotgun there do the gutting, since he’s entitled to call himself ‘doctor,’ too,” the woman said, ignoring the gibe.

J.B. doffed his fedora and scratched at his scalp. “You got training in cutting up folks. You told me so yourself. Everybody in med school did back in the day. Mebbe you just missed your calling.”

Mildred Wyeth, M.D., glared at the little narrow-faced man. “Yeah. Maybe I should have become a cutter instead of a researcher. Then I could have been rich, had a big house in the ’burbs, a nice docile hubby, two-point-five kids, a shiny new Caddy every year.” She looked thoughtful, scratched at her cheek with the very tip of her thumb, as if maybe if she did it gingerly enough she wouldn’t get gore on her cheek. She failed. “And then of course I’d’ve died while at the operating table instead of having a nice experimental cold-sleep pod on hand, to get slipped into for a snug century or so.”

“I’m glad you pulled through, Millie,” J.B. said quietly.

“Yeah, well at times like this I’m almost glad, too, even if I am stuck on shit detail. A little peace and quiet is doing us all a world of good. And bagging some good game without any taint of mutie doesn’t hurt, either. Sometimes it seems we’re in danger of getting too dependent on what we can scavenge from the redoubts or scam out of the villes. Woman does not live by century-old MREs alone. Or at least this woman doesn’t.”

“The boy stood on the burning deck!” the old man almost shouted.

“‘Eating peanuts by the peck,’” Mildred said.

The old man blinked at her.

“That’s the next line, Doc,” she said. “Trust me.”

“Quoth the raven,” Professor Theophilus Algernon Tanner said in a deflating kind of way, “nevermore.”

“And here I thought he was okay these days,” Mildred muttered, shaking her head as she returned to her grisly work.

“Doc,” the Armorer said with gentle firmness, “don’t go wandering off into neverland, now. We need you to keep a sharp lookout. Not had a whiff of anything menacing, two-legged or more, norm or mutie, in three whole days. And that very fact itself makes me uneasy.”

The old man nodded. His eyes seemed to have gained focus. “You are quite correct, John Barrymore. It’s when the illusion of peace and safety seems most perfect that danger draws nigh.”

“Yeah,” Mildred said bitterly. “Any state less than constant screaming terror just isn’t natural.”

J.B. nodded. “They don’t call these the Deathlands for nothing.”

RYAN CAWDOR LAY on the ground, with his bare feet planted in a lush mat of fallen Ponderosa pine needles, long and gracefully curved as sabers, held together at the bases in clusters of three. The freedom afforded by temporary safety, to take his boots off and feel untainted nature beneath his soles, was an almost erotic pleasure.

Krysty Wroth, the most beautiful woman of the Deathlands—and not just in her mate’s single prejudiced eye—lay on the ground beside him. Both were gloriously nude, enjoying a moment of closeness and solitude after an hour of lovemaking.

He marveled in the sight of her, her white skin given a faint golden luster by the sunlight filtering through the trees. He would never tire of her, could never imagine tiring of her beauty, her vitality, her untamable spirit.

Both of them were alert to their surroundings, knew from the soft forest sounds that no immediate danger threatened. Both also knew the interlude could last but moments, that they would need to pick themselves up and square themselves away too soon, because as Mildred had just observed, unheard by them, peace and safety were unnatural states in the Deathlands, unstable as an isotope of plutonium.

All the same, the Deathlands had taught them to make the most of any and all such moments they could tear out of the grim, potentially lethal fabric of their daily lives. He stroked her cheek. They kissed. “Time to go, lover.”

With a sigh of regret the lovers stood.

Ryan picked up his Steyr sniper rifle and stood guard, unself-conscious of being buck-ass naked, while Krysty dressed without either hurrying or dawdling. Then she took