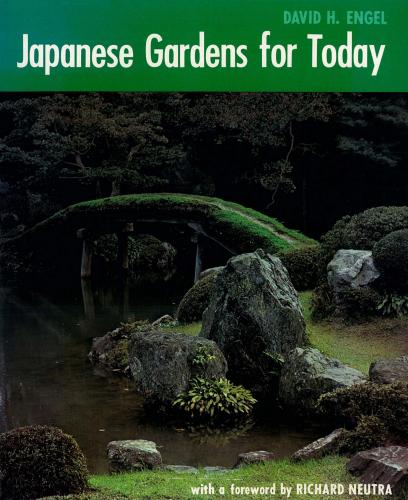

Japanese Gardens for today. David Engel

endocrine discharges and pleasant associations play through the visitor's body and mind as he views, and promenades. Or, even when he sits seemingly in full repose, that strangely emotive "force of form" that exists in the garden keeps eliciting the vital, vibrating functions of the subtle life processes within him that we call delight. All this is far beyond the effects worked on us by merely quaint, exotic decoration.

The author of this valuable book rightly warns against its being used superficially for the shallow imitation of fragments. The book's greatest benefit will be to stir an awakening to the unified appeal that results from such a profoundly integrated composition as a Japanese garden. This same principle of total appeal has also been practiced, often with completely unstudied innocence, from neolithic Machu Picchu in the precipitous mountains of Peru to Zulu villages in the African bush, but it has, alas, all but disappeared where our herds of bulldozers have bullied the landscape into a "marketable" product.

Japanese towns, villages, houses, and gardens are often miracles of land economy, brought about both out of necessity and from a general sense of thrift. This book gives much more than a glimpse of the "humanized naturalism" of the Japanese landscape, a landscape that proves that even a tightly massed civilization need not spell the defilement of the natural scene but, in fact, can mean its glorification.

Los Angeles, February, 1959

Acknowledgments

IT IS ALWAYS a pleasant task to thank those who have helped you. In this instance it can truly be said that it was the encouragement and generous assistance of many Japanese well-wishers that brought this book into being. Though it would be impossible to list them all, I shall never forget the many friendly, open doors of private homes and temples where I was always so cordially received. No matter how busy they were, housewives, homeowners, and temple priests were proud and happy to invite me inside, to show their houses and gardens, and to talk to me over a hospitable, warming cup of tea.

There are also those to whom I must especially express my gratitude. First, to Tansai Sano, artist, garden designer, and builder. He is a humble man of taste and sensitivity who, while deeply loving the rich heritage of his country's culture, still does not hesitate to try, with bright, creative originality, new forms of artistic expression in a garden. He is my teacher and my friend. With enthusiasm he accepted me as his pupil. With gentle humor and patience he-listened to my questions. And he taught me not only principles of garden design and construction, but also to see gardens as a joyful part of the human adventure.

I am also grateful to the Landscape Architecture Department of the Faculty of Agriculture of Kyoto University for the use of its well-stocked library. I am deeply indebted to Professor Eitaro Sekiguchi and his staff, and especially to Makoto Nakamura, who helped me with his friendly criticism and advice.

I am thankful also to the Faculty of Architecture of Tokyo University of Fine Arts, where I was registered; to Professor Junzo Yoshimura, who smoothed the way; to Professor Isoya Yoshida; and to Gakuji Yamamoto, for his encouraging and helpful letters.

As indicated below, for many of the photographs in this book I am obliged to Seiichi Sano, who is following in his father's distinguished tradition of garden building, and to Yoshio Takahashi, who spent almost two years photographing gardens all over Japan for the publishing house of Kodansha.

The staff of the City of Kyoto's Bureau of Tourist Industry were most helpful and cooperative in securing for me introductions and passes to many of the gardens. And, above all, with fondness and gratitude my appreciation goes to my friend Eiko Yuasa, of that office, who typed the manuscript for me and in countless hospitable, generous ways helped me during my stay in Japan. I thank my friend Kiyoshi Makino, the Tokyo architect, who allowed me to use the pictures of the Sassakawa, designed by him.

To Hiroshi Uemura, garden designer and builder in Kanazawa, who gave so generously of his time and whose name unlocked many a garden gate, I feel grateful obligation.

My thanks to Tadashi Kubo, of the Agricultural Faculty of Osaka Prefectural University, who sent me his compilation of the Sakutei-ku For their help with many of the drawings I am obliged to Shiotaro Shizuma and Shigeo Fujita.

I owe gratitude to the Japanese government, which awarded me, through its Ministry of Education, a grant to study garden design and construction in Japan.

And to the Japan Society in New York, which helped me to get started on this study project, I am most grateful.

The gardens of Messrs. Tomoda, Mizoguchi, Kaba, Watanabe, Tamura, and Ishida and of the Narita Fudo and the Kicho, illustrated in pages which follow, were designed and built by Tansai Sano. The garden of Mr. Akaza was designed and built by Hiroshi Uemura.

The sources of the photographs used in the book are as follows, all those not otherwise indicated having been taken by the. author:

By Seiichi Sano: Plates 1, 3, 19, 20, 28, 31, 37, 42, 43, 45, 48-50, 52-55, 59, 60, 63-67, 70, 78-80, 102-5, 112, 113, 121, 125, 127, 130-32, 135, 137, 139, 144, 146, 148, 154-56, 159, 161-63, 166, 176, 177, 181, 182, 184, 185, 187-89, 198, 202, 205, 207-9, 223, 232, 234, 236, and 265; and Color Plates 6-7 and 10.

By Yoshio Takahashi, and used by courtesy of Kodansha, Tokyo: Color Plates 1-3, 5, 9, 11, and 15.

Courtesy of the Bureau of Tourist Industry, Kyoto: Plates 72, 76, 97, and 193.

Courtesy of Kiyoshi Makino: Plates 24-25.

DAVID H. ENGEL

Japanese Gardens for Today

Introduction

SWIRLING out of the Japanese garden a fresh concept of design is running strongly through today's landscape architecture. This lively current forms part of the broad stream, of ideas emanating from the Orient and especially from Japan's seemingly inexhaustible wells of art. In the past few years Occidental architecture and design have been subjected to steady contact through such extensive importation of Far Eastern influences that at times they have appeared to be almost inundated. The responsibility of pointing out the misinterpretations, downright fads, and nonsense in the "Japanese trend" rests with the designers and architects. It remains, of course, for each artistic discipline to study new ideas and practices, to guard against the introduction of the tasteless and irrelevant, and to select from the mass of things what is valid and beautiful.

For landscape architecture and garden design, then, this book is intended to serve as a guide on the subject of Japanese gardens. It shows many kinds of gardens as illustrations of design principles. Its immediate purpose is to provide both professional landscape architects and amateur garden builders with a handbook to help them in their work. The aim here is to stimulate the imagination and to suggest a challenge.

The scope of the book differs from previous works on Japanese gardens in that it neither offers general and abstruse esthetic critiques and interpretations of famous Japanese gardens nor does it delve into their religious, romantic, and historical associations—though in their place these too are fascinating. The Japanese garden is treated here, not as a quaint, exotic, Oriental bird, hut as a living, artistic structure with important significance for people in countries outside of Japan.

The book is the product of on-the-spot research and study and the practical experience of working with a master garden artist—an apprenticeship in design, construction, and plant care—extending over almost two years in Kyoto and other parts of Japan.

Today's widespread interest in garden art is a healthy sign. But of even more significance is the fact that it is the Japanese garden which is causing much of the ferment. Thus there is evidence not only of evolution in the field—a search for better forms in landscape design—but also of rejection, perhaps on both subconscious and conscious levels, of materialistic principles in gardening and landscaping. It may be that this heralds an awakening to the need for gardens which can stimulate responses that spring from our innermost recesses.

The paradox of the mid-twentieth