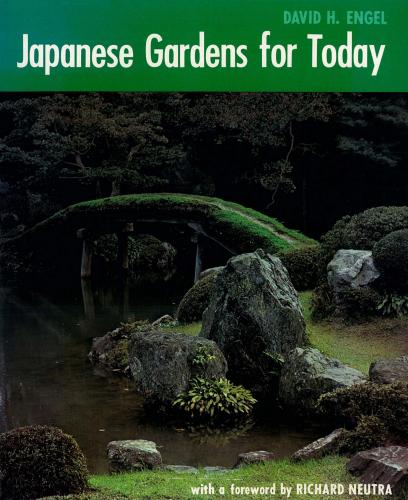

Japanese Gardens for today. David Engel

The elements of the Japanese garden are not just dramatic garden props, used for easy upkeep and unique effect. If it were so, the garden would be merely a clutter of things, sterile, insincere, false. Above all, a good garden has naturalness, strength, simplicity, humor, and human warmth. Its elements are arranged to convey the feeling of the partnership of nature and art. In effect, the symbolism is that of man and nature in a pact of friendship, sealing it, as it were, with a hearty handshake.

You do not have to be a lover of Japanese culture to be able to grasp some strong validity in its garden art. From the standpoint of pure design it is logical and honest. But, more than that, its bonds are stronger and its roots deeper than any we have known heretofore in the realm of garden art. They are ties of an ineffable spirituality, which can be felt at all levels of perception. And this forms what may be the real attraction of Japanese gardens at this critical juncture of Western cultural growth.

PART ONE

The Theory:

WHY & WHAT?

1. Some Universal

Garden Effects

WE ARE children of nature. But since the dawn of life we have come a good distance. Our human civilization down through the years has evolved into ever more intricate and complex urban patterns, in which steel and concrete have come to play the predominant role. Though it seems obvious that at least one foot is irretrievably stuck in the hard city pavement, the other remains just as solidly planted in the moist, soft earth. We will never give up loving nature, wanting some quiet, beneficent refuge to go back to when the "world is too much with us." And so we have made gardens.

A garden offers us security. It is as if a kind power instilled in a garden has come around to preserve us. We do not, of course, respond to all manifestations of nature with indiscriminate trust and open arms. From the very beginning we have made the distinction between nature in the raw and the humanized landscape. In the midst of untamed wildernesses of forests, mountains, plains, swamps, deserts, tundra, or jungle we are struck with awe by the power and majesty of nature expressed in great stretches of uncultivated terrain, untouched or ungentled by man.

Such feelings are altogether different from what we experience in a pleasant spring meadow surrounded by the sights and smells and sounds of farm life. Or, lying under an apple tree whose fragrant blossoms pour out their perfume into the burgeoning spring air, we feel some upsurging energy, a link with nature's creative drive. Any bit of humanized landscape, whether it be large or small, elaborate or simple, used for flowers, fruit, vegetables, or grazing, has qualities of a garden; and, as such, can be enjoyed in varying degrees and ways according to our special interests, experience, and sensitivity.

But, although a farm may offer us nature in a humanized setting, we know that a farm and a garden are not the same thing. The former is designed with a view to the practical requirements of an efficiently producing agricultural unit; while the latter is made, not for economic gain, but with a view to esthetic values and to serve a purpose offering no direct economic or material benefits. The value of a well-designed garden may be judged only by the subjective effects it produces on the people who use it. It might be an effect of pleasure caused by some esthetic perception; an effect of convenience, leisure, or repose induced by some direct sensory experience in the garden; an effect of spiritual enrichment, the result of some mystic inspirational process; or, depending upon the individual, the time, and the place, it might be combinations of all of these effects in varying proportions and strengths. It is evident then that while the appeal of a garden is universal, the effects it may produce depend upon its location and its particular individual character. The latter is in turn the product of local tradition, customs, and the way the garden was designed to be used. The personality of the user is the final determinant.

What, then, are those desirable garden effects that have pleased men in all times and all places? Let us consider them in the following paragraphs.

Space & Vista. We love the effect of spaciousness and vista. Looking across long, unrestricted distances, we gain a feeling of freedom. As we gaze at a far horizon our imagination takes flight. But we also like our privacy.

Of course, if our garden is located in a sparsely populated area, such as desert, mountain, seashore, or woods, we may be able to combine both vista and privacy. A home perched on a hillside or mountaintop gets complete privacy as well as a mountain view. (See Plate 2.) These days, homes are being built on the edges and even in the midst of the American desert. The sand and rock, mountain and basin, of the desert, in all its changing moods and colors, enter into the garden design and become a part of it. And probably this is what the people who live there like most about their environment. They moved to the desert to gain both privacy and a view.

Privacy. In other instances, a sense both of space and vista and of privacy are mutually exclusive. If we gain one, we lose the other. Anyone with a garden in an urban or semi-urban area, where houses are relatively close together, and who insists on freedom to enjoy his house and garden as he pleases, will require some kind of enclosure. Fences limit his view but substitute for it a sense of personal freedom. This is certainly a desirable effect that becomes necessary as we live more and more in our "outside room." It is, in fact, more democratic to put up a wall, fence, hedge, or plant screen than to live constantly within the sight and sound of our neighbors. With no privacy in our garden we feel constrained and inhibited by fears of annoying our neighbors or of incurring their disapproval. But by simply erecting a barrier the problem is solved. Each may now live his life as he sees fit, with no interference from or disturbance of the people next door. Enclosure also induces a pleasing effect of repose and tranquillity by cutting out distracting outside noises and sights (see Plate 3). Finally, it defines the limits of a garden, just as a frame sets off a painting, thereby enhancing its beauty.

Color Plate 3. Nature and art met here six hundred years ago when this garden was first created. Since then, the trees have passed through more than one generation of planting. Through the high overhead limbs the light filters through to the ground, providing the partial shade that is the perfect condition for the moss that now holds sway. But the hand of man, though ever so lightly applied, is still at the controls. (View from Koin-zan, Saiho-ji, Kyoto.)

Color Plate 4. This is not a wild, wooded glade. It is a gentle land scape constructed about six hundred years ago as a "stroll garden'' for a temple built at the foot of a wooded hill. The ground cover is moss of many species, which long ago took over from the rocks set in the banks of the pond and a long its paths. The trees are principally pines, maples, and evergreen oaks interspersed with spring -flowering trees and shrubs and bamboo. (Soiho-ji, Kyoto.)

Age & Antiquity. A sense of age and antiquity is another garden effect. We love to feel that things embody tradition and continuity with the past. We thereby gain roots. It is an assumption of dignity and substance, of a well-established place in our society. We treasure our antiques. An old house or a venerable landmark evokes a kind of nostalgia in us. We have the feeling that we would like to live there, if not to possess it. (See Plates 175, 187, 188, 194, and 197.)

Rhythm of Nature. We see the imperishable, the never-ending rhythm of nature manifested in the elemental forces which are always at work even in the most insignificant details of a garden. Thus, after a long, cold winter we are reassured of nature's power and cyclic beat on first seeing the tender buds of the crocus pushing their heads up through the residual snows of March and April. It is a promise of the renewal of the seasons. Equally heartening is the feeling we experience standing in a grove of California's giant redwood sequoia, listening to the wind sighing through the towering treetops.

Imagination. A garden which stirs the imagination has precious vitality. This effect requires that everything not be revealed to complete view from any single vantage point. The spectator is left to imagine what lies behind a hedge, a turn of the path masked by an artful arrangement of shrubs and rocks, the winding thread of a murmuring brook whose banks can be only partially seen from any